Ti 題 and ba 跋 are forewords and afterwords when accompanying books, but they are also used to introduce and annotate paintings, calligraphic works, and rubbings of inscriptions. In all cases, ti have the character of prefaces or introductions, and the somewhat shorter ba are placed at the end of a text or an artwork. Scholars discern between different contents of prefaces, like titles (biaoti 標題), ratings (pinping 品評), critique (kaoding 考訂) or remarks to the idea, content and background (jishi 記事). They might be written in prose or in a poetic style. Titles of books written in calligraphic style instead of typesetting are also called ti.

The use of ti and ba for artworks began during the Song period 宋 (960-1279). Prefaces might have a substantial length, as that of Wang Mian's 王冕 (1287 or 1310-1359) painting Dianshui meihua tu 點水梅花圖 with a length of nearly a thousand characters, which includes a biography of "Master Mei" (Mei Xiansheng zhuan 梅先生傳). Other examples of long prefaces are the artworks of Bada Shanren 八大山人 (1626-1705) and Shi Tao 石濤 (1641-c. 1707) of the Qing period 清 (1644-1911). From the Yuan period 元 (1279-1368) on, it was common to add poems to paintings.

|

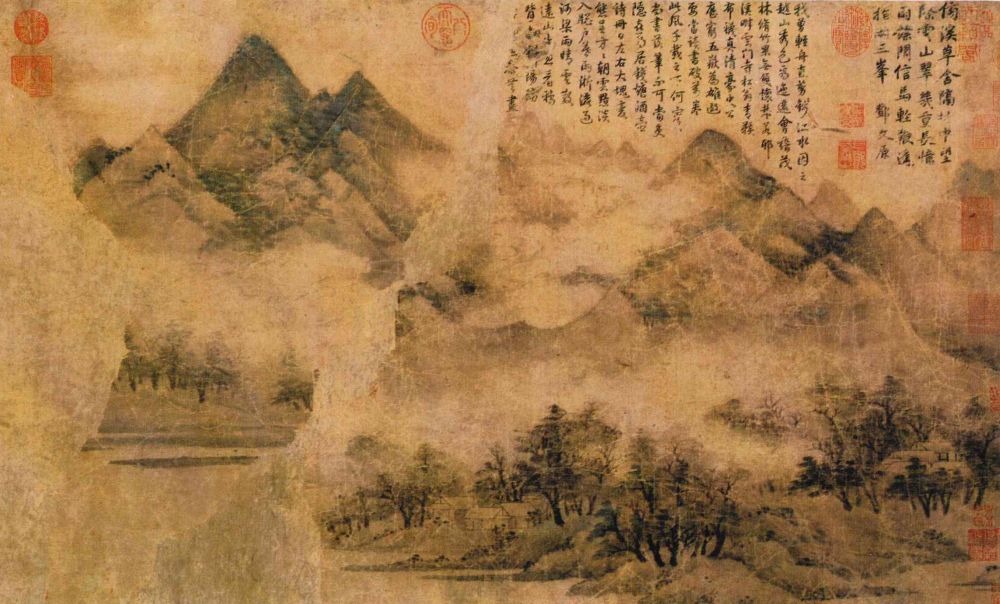

Gao Kegong 高克恭 (1248-1310), "Qiushan mu'ai tu 秋山暮靄圖" (Evening haze in autumnal hills). The scroll includes a poem of Deng Wenyuan 鄧文原 (1258-1328) especially written for this painting (tishi 題詩). Another, much longer text (tiji 題記) has been added much later by the Qianlong Emperor 乾隆帝 (r. 1736-1795). From Zhongguo meishu quanji bianji weiyuanhui 中國美術全集編輯委員會, ed. (1992), Zhongguo meishu quanji 中國美術全集, Huihua bian 繪畫編, Vol. 5, Yuandai huihua 元代繪畫, (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe), no. 10. |