China is today the largest trading nation of the world. In 2006, its trade volume in in- and exports made out 65 % of the GDP (Naughton 2018: 397), which is about three times as much as in most other industrial states. The most important factor contributing to this phenomenon is the low labour cost needed for assembly or production of items like clothes, shoes, toys or knick-knack. The low price of labour cost is caused by the abundant reserve of migrant workers coming in from the countryside, at least until the turn of the century. This constant flux has recently dropped in numbers (see human capital), and the factor of labour becomes more expensive. A second item of factor endowment in China is the relatively advanced educational system which produces not just workforce for manual labour at assembly lines but also lays the foundation for the fostering of technicians and managers (see innovation).

The proceeds of the export business serves to import food and raw materials. For foreign importers, the sheer size of the China market continues to represent an attractive reason for investment. Yet even a market as large as the Chinese one shows in some fields symptoms of satiation, and suffers of unexpectedly low demand in some fields. The weakness of the domestic market is the reason for China's growing abroad investments as for instance in the Belt-and-Road Initiative (yidai yilu 一带一路) that was initiated in 2013.

With the accession to the WTO (Ch. Shijie maoyi zuzhi 世界贸易组织, short Shimao 世贸) in 2001, China has become a "mature market economy". Nonetheless, China still carries out protectionist policies, for instance, providing state-owned enterprises easier ways for funding, or restricting the access of foreign enterprises to certain market segments like public procurement. Domestic players are often preferred over foreigners.

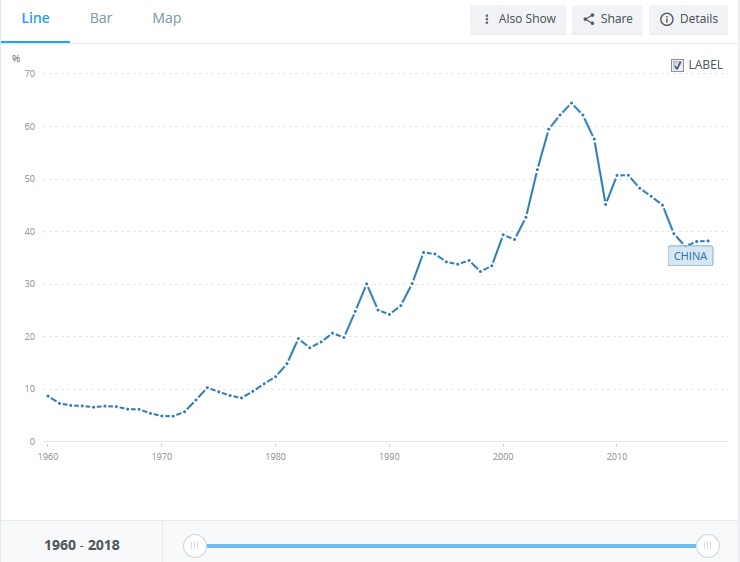

|

Foreign Trade (% of GDP). World Bank 2020. |

With the foundation of the People's Republic in 1949, China "leaned on one side" (yibian dao 一边倒) towards the Soviet Union with which a Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance was signed in February 1950. Throughout the decade, 48 % of China's trade was carried out with the Soviet Union which made out 12 % of the GDP (Naughton 2018: 398). The split with the Soviet Union in 1960 made necessary the approach to new trade partners of developed countries, mainly Japan and some European states. China imported machinery and technical products and exported agricultural products, light-industry products and mineral resources (MacDougall 1972; Chen 2006; Mah 2017). Yet this trade stood only at 5 % of GDP (Naughton 2018: 399). From the mid-1970s the import of machinery was barter trade paid by oil.

With the beginning of the era of Reform and Opening (gaige kaifang 改革开放) in 1978, and particularly after the WTO accession in 2001, China's foreign trade experienced a constant increase, even if the Asian Financial Crisis (Ch. Yazhou jinrong fengbao 亚洲金融风暴) of 1997 somewhat depressed imports. The rapid increase of the foreign trade sector reached 35 % of GDP (Naughton 2018: 400) before experiencing an abrupt end in 2007 with the Global Financial Crisis (Ch. huanqiu jinrong weiji 环球金融危机). The share of foreign trade in the Chinese GDP is constantly decreasing since that time and amount presently at good 10 % (Naughton 2018: 401). Yet China's share in global exports continues to rise and makes out 10 % of global trade (Naughton 2018: 401).

Imports and exports in China were in the beginnings strictly tied to state-owned foreign-trade companies (FTC, waimao gongsi 外贸公司). The Chinese currency, the Renminbi 人民币 (RMB) accounted in Chinese Yuan 元 (CN¥), was not convertible. FTCs purchased and sold according to plan and converted their planning prices before and after each transaction into RMB. According to the political guideline of import substitution (preferring local production over imports, if possibly by local alternatives), just urgently needed goods were purchased on the world market in the early 1980s.

The first step of opening up the economy was to allow Hong Kong firms to conclude contracts with Chinese enterprises in the Pearl River Delta for export processing. Component parts were shipped from Hong Kong (and Taiwan soon, also) to Guangdong, where they were assembled and then exported again to the the country of the producer. All parts of the commodity remained ownership of the Hong Kong producer and were just assembled in China with her cheap labour force.

In 1979, the four Special Economic Zones (jingji tequ 经济特区) of Shenzhen 深圳, Zhuhai 珠海, Shantou 汕头, and Xiamen 厦门 were founded, the first three being coastal cities in the province of Guangdong, the last in Fujian. The zones imported goods free of duty, processed, and then reexported them. This measure contributed immensely to the the economic development of the southeastern coast region, and the provinces of Guangdong and Fujian were dubbed the "fifth tiger", to be added to the four economic climbers of the Four Tigers Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, and Taiwan.

All "five tigers" were characterized by common features, namely Confucian work ethic (compare the famous essay of Max Weber), cheap workforce, an entrepreneurial middle class, special economic zones, favourable access to the world market, and all of them were steered by "development dictatorship" (a concept from the 1960s). A similar example, Japan, advancing somewhat earlier to an export-oriented country had profited from protectionism of domestic concerns and foreign financial support, differs from the Four Tigers as the country had built up an industrial base before 1945 (Crawcour 2008).

In the 1980s, China's politicians pursued for measures to farther open the Chinese economy, namely the adaption of the exchange rate of the RMB to the US$, the de-monopolization of the foreign trade (abolishing FTCs), the liberalization of import prices, and the creation of a decent customs and tariffs system.

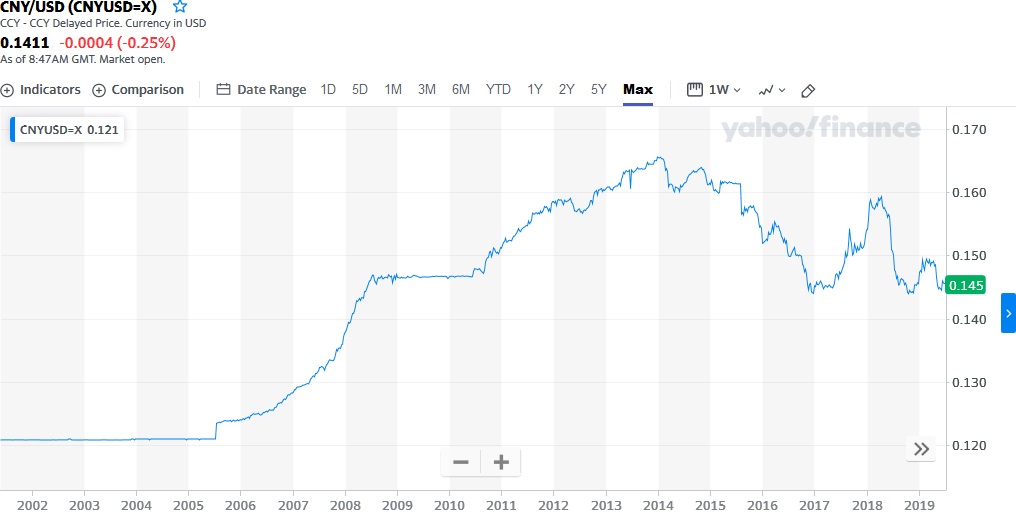

In 1980, the RMB was strongly overvalued with an exchange rate of 1.5 ¥/$. Until 1985 it lost half of its value. At the same time, an internal settlement rate was applied which was lower than the official rate and thus made export business cheaper. A lower swap rate allowed favourable conditions in exchange processes. Until 2007, the RMB was pegged to the US$, with an exchange rate of 8.27 ¥/$ (Naughton 2018: 406). In 1994, the RMB was given free for free exchange and listing in the current account.

Between 1980 and 1995, tourists had to make use of the parallel currency Foreign Exchange Certificates (waihui duihuan quan 外汇兑换券, FEC) which was denominated in RMB, but had a different exchange rate. This currency was aimed at preventing the emergence of currency black markets, made easier the drawing up of balance sheets, allowed for better control of exchange rates, and allowed the tourist industry to reap profits, as the FEC exchange rate profited the Chinese currency.

During the Asia Financial Crisis in 1997 the RMB came under slight devaluation pressure, but to a far smaller extent than the Japanese Yen ¥, the Korean Won ₩ or the Baht ฿ in Thailand. Thereafter, the RMB was more or less tied to the US$. Free floating was begun in 2005, and the RMB was progressively upgraded. Some actors had claimed that China kept the value of the RMB at an artificially low level in order to boost exports. The official designation of China as a currency manipulator was given up in early 2020 (Rappeport 2020).

Tyers and Zhang (2010) demonstrate that a currency has not necessarily to be appreciated as required by the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis, which holds that a raise in commodity production does not just influences a rise in prices of commodities, but also in services. The relatively low value of the RMB – in spite of high production quota – can be explained by a high savings quota and the imperfect conditions of China’s financial markets.

|

Price of RMB in US$. Yahoo Finance, as of 27 March 2020. |

The liberalization of international trade was first realized by the creation of ministerial FTCs, then of local ones, also in the SEZs. In 1988 finally, when there was a total number of 5,000 institutions and 10,000 enterprises allowed to engage in foreign trade (Naughton 2018: 406), export and import were given free, and world-market prices were applied instead of Five-Year-Plan prices.

In the early 1980s, a high-tariff customs system was introduced, scaring off potential Chinese buyers to purchase foreign goods. In addition to high customs duties of 32 or 45 % (Naughton 2018: 407), non-tariff barriers on trade prevailed, for instance, the monopoly of the FTCs over the import of consumer essentials or the right of manufacturing firms to import only for their own production needs.

From the mid-1980s on, foreign enterprises were allowed to conclude directly contracts with Chinese firms of the coastal provinces. Raw materials could be imported duty-free, but remained ownership of the foreign part. The export-processing industry in the coastal provinces, cooperating mainly with firms from Hong Kong and Taiwan, grew much faster than ordinary, domestic industry. In 1996, 56% of exports were generated by the specialized export-oriented industry (Naughton 2018: 408).

Apart from contracting Chinese firms for processing and assembly, foreign direct investments grew rapidly in the coastal provinces and in 2003 outpaced Chinese investment in export-oriented business, even if the latter were given the same export conditions as FDI enterprises in 2001with China's accession to the WTO.

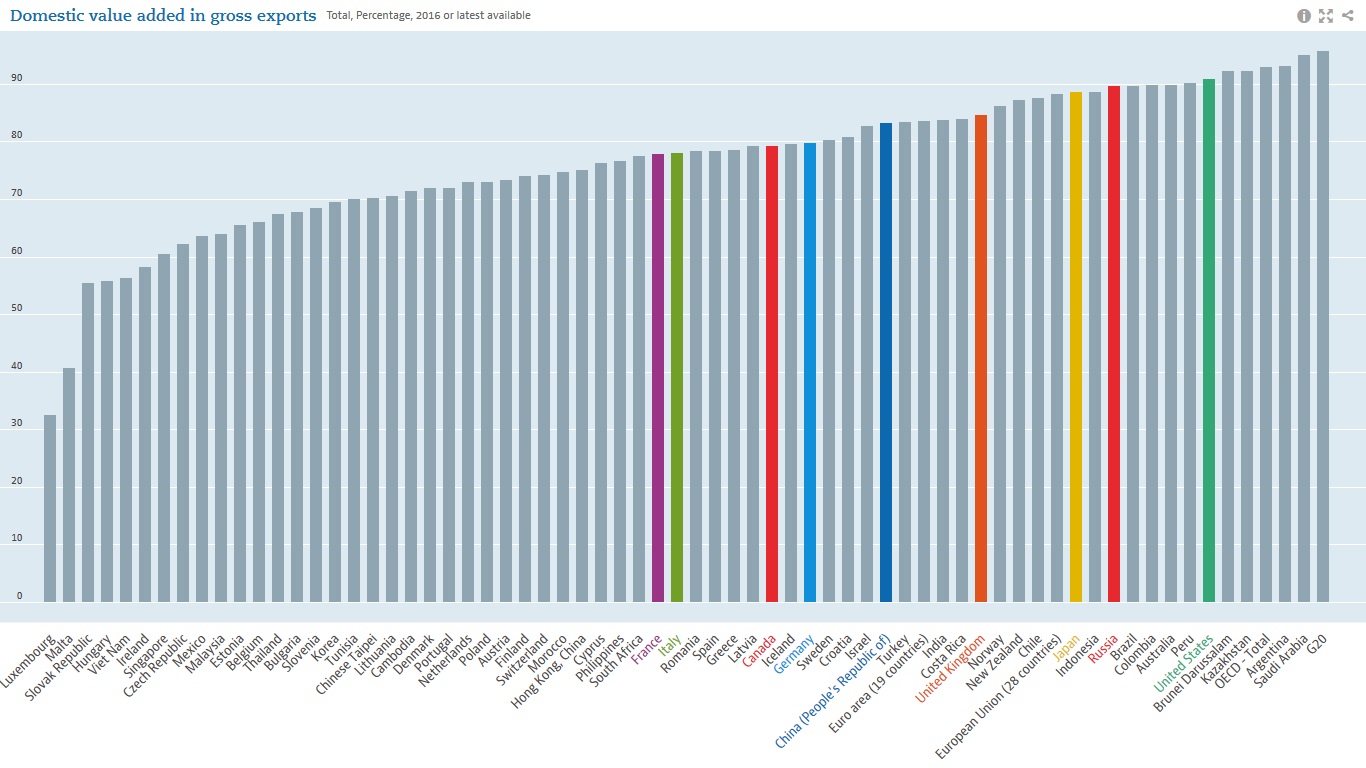

Between 2005 and 2014, the export volume of the export-oriented industry doubled. Regardless of the huge numbers, the greatest part of Chinese exports was found in the lower levels of value-added chains (VAC). This means that China remained the "workbench" of the world without rising to higher levels of technical and industrial sophistication. Moreover, turnover is relatively low in the lower levels of the VAC, and becomes even thinner with growing labour costs.

|

In %, China (dark blue) and G8. OECD (2020). |

One important pillar for China's WTO entry was the creation of a sound value-added tax system. This would allow China to sell agricultural produce and products of the light-industrial sector on the world market, and protects foreign investments in China in a better way.

In 2004, the Foreign-Trade Law (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo duiwai maoyi fa 中华人民共和国对外贸易法) was promulgated according to which only a few agricultural products continue to enjoy protection. Most customs duties – until then amounting to no less than 43% - were lowered, first to 17 %, then to 9.4 % (Naughton 2018: 412).

The fear of some Chinese actors that the domestic industry would collapse after the WTO entry proved to be unfounded: China experienced since 2001 a gargantuan boom in foreign trade. Chinese imports into the US tripled after 2001 and provoked an American trade deficit of 259 billion US$ in 2007 and 419 billion US$ in 2018 (Naughton 2018: 413). The Trump administration, being alarmed by this deficit, began therefore a policy of raising tariffs and duties, or a "trade war". In China, foreign trade made out 7% of the GDP in 2006 and levelled off at 2-4 % thereafter (Naughton 2018: 412). China has a foreign trade surplus against the United States, Japan, and the EU as a whole, while it imports more from Korea and Taiwan than it exports there.

Until 2000, China mainly imported raw materials, intermediate goods and components, capital-intensive materials as steel, chemical products, synthetic fibres and plastics. Such goods constitute today just make out 17 % of all imports (Naughton 2018: 415), while mining products and natural resources like ore, gas, mineral oil and fertilizer play an increasing role, along with production machinery, transport tools, and electronics. Since the WTO entry it is mainly machinery and electronic products, i.e. commodities requiring capital and technological skills. Clothes and labour-intensive goods which were dominant in the two decades 1980-2000 only stand at 10 % of exported goods (Naughton 2018: 414). Rising wages caused the producers of such commodities to migrate to western provinces with cheaper labour cost like Henan, Chongqing, or Sichuan.

High-technology products play an increasing role in China's export business. It ranges from an excellent network of markets and suppliers in the country, but also covers the export of hard- and software to foreign countries, for instance, the 5G telecommunication standard supplied by Huawei to various European countries. Yet in some points, data about Chinese high-tech exports are misleading, as 85 % of them are produced by foreign-invested enterprises (FIE) in the frame of the export-processing regime created in the past decades (Naughton 2018: 417). Moreover, China's contribution in this sector is assembly, and not creation, and is thus part of a low value-added process. This situation is quickly changing, and China begins to climb up the ladder of higher value-added products.

The service sector also plays an increasing role in foreign trade, especially the import of tourist services due to the growing desire to travel of the Chinese and the high number of Chinese students abroad and possibly also due to capital flight. However, the freedom to provide services is still underdeveloped, especially in the finance and insurance sectors, but also in other business areas. In the realm of FDI, China restricts foreign access to important parts of the service sector. Less than half of the incoming FDI in China are related to services (Naughton 2018: 439).

In order to attract FDI, China had to allow capital flows. As a result, China is today one of the world’s most important destinations for FDI, but the share of incoming FDI has declined, but new forms emerged, mainly in the shape of outbound investments. China therefore accumulates foreign reserves until 2011, and various financial flows out of China, private as well as public, increased.

FDI had tradition since the "semi-colonial" period, mainly in the foreign concessions in Shanghai and other trade cities. During the Mao period, there were a few joint venture firms with other socialist countries. Establishment of SEZ, first used by HK and other Chinese overseas’ firms, but soon also Japanese and Western ones. After 1992, geographical restriction for FDI was gradually lifted, and other sectors than export manufacturing were opened, for instance, real estate. In order to encourage foreign investors, Deng Xiaoping embarked on his famous southern tour to dissipate doubts about China’s political reliability after the Tian'anmen Incident of 1989.

From that time on, the share of FDI in China's GDP decreased continuously from 6 % in 1994 to somewhat more than 1 % nowadays (Naughton 2018: 425). This trend follows the situation in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, while in Southeast Asian countries like Thailand, Malaysia or the Philippines, the export share of GDP still lingers at 6 %. Yet inside China, there are huge regional differences, with the "open" provinces of the Southeast coast showing a much higher dependency on the FDI. In China, FDI accounts for no more than 3 % of total fixed investment in China since 2012 (Naughton 2018: 431). The presently low significance of FDI for the Chinese economy might be interpreted as a symbol of decreased openness, in spite of the WTO accession in 2001.

The function of SEZ for the nascent Chinese market economy was to provide space for a double-track economy with market liberalization on the one hand and conventional state planning on the other. When the early five SEZ were founded, this measure found critique from the conservatives who saw in the zones a revival of the colonial foreign concessions, and a derogation of Chinese sovereignty. Yet these apprehensions were silenced with the increasing economic success, and the model of test zones continues to serve for development purposes, as can be seen in the Pilot Free Trade Zone in Shanghai (ziyou maoyi shiyan qu 自由贸易试验区) founded in 2013.

The idea of the zones themselves came from other Asian countries, where export-processing zones (Ch. chukou jiagong qu 出口加工区) served to boost the export-oriented manufacturing industry by means of low taxes, simplified administrative procedures, easy customs procedures, duty-free import of components for assembly, and free from export taxes. Investors were attracted by tax holidays, reduced income taxes (in China at a statutory rate of 15 % on profits; Naughton 2018: 429) and by the providing of ready-made infrastructure, in the case of the Shanghai Pilot Free Trade Zone even including hospitals, logistics, and insurance. Such zones had been created in Taiwan (Kao-hsiung, founded 1969), Malaysia (Bayan Lepas in Penang, 1972), Indonesia (Batam Island, 1973/2006), and the Philippines (Bataan, 1972), and all of them served as test beds for the liberalization of local economies.

In the early 1990s, the experiences from the five SEZs encouraged the Chinese leadership to spread the model to other places. Most famous is the Pudong (East Shanghai) Special Zone (Pudong New Area, Pudong xinqu 浦东新区) founded in 2013. Other zones were founded in Tianjin and the provinces of Fujian, Guangdong (2015), Liaoning, Zhejiang, Hubei, Henan, Chongqing, Sichuan, and Shaanxi (2017), as well as in Hainan (2018). Today, there are hundreds of zones, including 54 national-level economic and technological development zones (guojia ji jingji jishu kaifa qu 国家级经济技术开发区), 53 nationally recognized high-tech industrial zones (gaoxin jishu chanye kaifa qu 高新技术产业开发区), and 15 bonded zones (baoshui qu 保税区) to stock commodities outside the customs borders (Naughton 2018: 428-429).

Foreign investors are allowed to operate in practically all business fields, baring those on a negative list which includes general business fields as mining, the exploitation of wildlife resources or printing publications, but also the production of certain items like rice paper or ink ingot production (FDI China 2019; Zhang 2019).

The tax system of China was gradually adapted to the requirements of the needs of an export-oriented economy. The tax reform of 1994 unified the tax rates for domestic firms, but a unified enterprise income tax was only made applicable for foreign investors in 2008. Since 2012, a national profit tax of 25 % for both domestic firms and FIEs is valid. The latter are since also subject to local infrastructure taxes, social security taxes, and educational surcharges. With these changes, the overall attractiveness of special zones decreased somewhat.

On 1 January 2020, the new China Foreign Investment Law (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo waishang touzi fa 中华人民共和国外商投资法) came into force. It aims at better protecting the rights and interests of foreign investors and standardizing management of foreign investment, but the law still lacks implementation details on how to protect the legitimate rights and interests of foreign investors (Maurits 2020).

The main advantages of FDI are the transfer of funds, skills, expertise, technology, marketing channels and management techniques. Moreover, in financial terms, FDI are long-term investments not being subject to sudden changes in economic conditions. Foreign investing enterprises contributed two-thirds of the overall increment of Chinas exports until 2005 (Naughton 2018: 431). In developing countries, FDI is a crucial factor for the spill-over of technology and expertise for other sectors of the economy via the network of suppliers. Another positive aspect of FDI is the stimulation of competition in the domestic economy which can not only help to hold prices down, but also to clear the market from uneconomical firms. For China, this was particularly important in the second half of the 1990s, when many state-owned enterprises were "allowed" to vanish.

The largest FDI investor in China were Hong Kong firms. Out of the cumulative total of 1.8 trillion US$ of FDI until 2016, HK enterprises contributed half, while the share of enterprises from the US, Japan, and the EU was only 17 % (Naughton 2018: 433). Investments from “tax paradises” as the British Virgin Islands, Samoa, or the British Cayman Islands are often indirect funds from Taiwan, but also from the US and Great Britain. This leads to distorted figures in FDI statistics. The US invested 228 million US$ so far which corresponds to about 10 % of incoming FDI to China (Naughton 2018: 435).

The case of HK is quite special because the British colony has been returned to China on 1 July 1997 and is therefore actually not a foreign country. But free-market Hong Kong has a substantially different economic system than the PRC and was at that time deeper embedded in the global economy, for instance, as manufacturing basis for quite a few foreign-owned enterprises. This is still the fact nowadays, with 1,400 foreign headquarters located in Hong Kong (Naughton 2018: 436). Yet also some Chinese firms have been active in the city state for a long time, for example, China Resources (Huarun jituan 華潤集團) or China Merchants Group (Zhaoshangju jituan 招商局集團). The important Hong Kong Stock Exchange (Xianggang Lianhe Jiaoyisuo 香港聯合交易所) has been in operation since 1891. The other way around, Hong Kong enterprises have been granted special privileges on the China market since 2003, when the Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (Neidi zu Xianggang guanyu jianli geng jinmi jingmao guanxi de anpai 内地与香港关于建立更紧密经贸关系的安排, CEPA) was signed (Trade and Industry Department).

Common language and culture made it much easier for enterprises in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore (Greater China) to shift parts of their manufacturing, especially the labour-intensive parts, to China. In the beginning, the products manufactured in China were textiles, shoes, plastic products or spare parts, but since around 2000, a great part belonged to the high-tech sector. In the course of the past decades, Hong Kong was de-industrialized and shifted to services and financial business, while the coastal provinces of China were industrialized. The economies of the countries of this "China circle" (Naughton 1997) are deeply integrated by various layers of supply chains.

Outbound FDI play an increasing role. In the first years, Chinese FDI was focusing on natural resources and was cominated by the large SOEs. Since 2016, outbound FDI outpaced incoming ones and are increasing steadily. The reason for this huge increase are the search for new markets (facing domestic market satiation e.g. in the construction sector), the adoption of foreign expertise and technology by purchase of whole firms or shares, or mergers and acquisitions, but only to a small extent greenfield investments (building own factories). Also in the case of outbound FDI, Hong Kong is the foremost target, but industrial states became a new target after 2016, with 130 billion US$ (Naughton 2018: 440) in the United States, followed by Australia, Canada, and Brazil. Chinese SOEs invest in industrial projects as metals, ore extraction, real estate, transport, and finance.

In 2013, China launched the Belt-and-Road Initiative (Yidai yilu 一带一路 "One Belt One Road") with the purpose to invest heavily in infrastructural projects in Central Asia, but also in Europe, Africa, and even Latin America. Many countries welcome Chinese investment as a means to promote their economic landscape. Chinese investment creates jobs and infrastructural facilities. Not all investors are state-owned by name, but many private firms like Huawei are deeply connected with state actors and investors. Four large Chinese firms accounted for 18 % of Chinese FDI: Anbang Insurance, Dalian Wanda, Fosun, and Hainan Airlines (Naughton 2018: 441).

China does not have an open balance capital account which makes is difficult to trace the flow of funds to and from China. Some outbound FDI are subsumed unter the item "others". Generally spoken, the balance f trade in goods and services has been positive in the past years, making out 2-3 % of the GDP, as is normal for an exporting country. Net FDI has become negative since 2006, meaning that China invests more abroad than foreign actors invest in China. The holdings of official foreign exchange reserves is negative, meaning that China accumulates reserves and invests these in low-risk securities like U.S. Treasury bonds. Financial flows are very large, but highly volatile, but three period can be determined

| Balance of Payments (Guoji shouzhi zhanghu 国际收支账户) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Current Account (jingchang zhanghu 经常账户 | Capital Account (jinrong zhanghu 金融帐户, ziben zhanghu 资本帐户) | Foreign Exchange Account (waihui zhanghu 外汇帐户) |

| Goods, services, income, current transfers, donations | FDI, portfolio investment, financial derivatives, short- and mid-term capital movements | capital reserve, gold, funds at IMF |

Throughout the 1990s and until the WTO entry, capital was leaving China. The trend was reversed thereafter, and China's booming economy attracted investments of foreign capital, also by the hope that the RMB might appreciate. China had a large trade surplus until 2010 which it sought to balance by buying massive amounts of foreign exchange, at a rate of 10 % of GDP annually (Naughton 2018: 444). After 2012, the trade surplus shrank to 2-3 % of GDP, but capital left China (c. 700 billion US$ p.a., which is ten times as much as in the late 1990s), often for speculative purposes. The official foreign-exchange reserves steadily rose until 2014 (at that time nearly 4 trillion US$) before they began to tumble.

The RMB is convertible on the current account, but not as a tradeable currency on the capital account. As a net exporter, China must also export capital. Capital outflows are the result of domestic saving being hight than domestic investment. The accumulation of foreign exchange, caused by a trade surplus and incoming FDI, helped to keep low the exchange rate of the RMB, this is turn making Chinese exports relatively cheap. Yet this accumulation must be balanced by issuing domestic currency, which has the danger of inflationary pressure. Finally, foreign exchange reserves are usually invested in low-return Treasury bonds as a large and almost exclusive investment strategy. The Chinese government therefore pursued a different strategy after 2014 to get rid of its huge treasury of foreign exchange.

One solution to get rid off the accumulated foreign reserves is outbound investment. For this purpose, China has set up some funds - some of them in an international setting - to collect and channel investment money. Such funds are the sovereign wealth funds operated by the China Investment Corporation (Zhongguo Touzi Ltd. 中国投资有限责任公司, CIC, 2007) and the SAFE Investment Company (Hua'an Touzi Gongsi 华安投资公司, 1997) of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (Guojia Waihui Guanliju 国家外汇管理局, SAFE). Multilateral instruments became more important thereafter, with the Silk Road Fund (Silu Jijin 丝路基金, 2014) or the Asian Infrastructural Investment Bank (Yazhou Jichu Sheshi Touzi Yinhang 亚洲基础设施投资银行, Yatouhang 亚投行, AIIB), in which China contributes 30 % of the capital and holds 26 % of the votes (Naughton 2018: 447). In 2014, the BRICS Bank (Jinzhuan Guojia Kaifa Yinhang 金砖国家开发银行, official name New Development Bank, Xin Kaifa Yinhang 新开发银行) with its headquarters in Shanghai was created to direct Chinese capital to the other BRICS states (Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa).

At the same time, the government reinforced regulations for capital outflows to stabilize the currency, but in this way restricted the envisaged liberalization of the capital account. The only way to achieve this target is the enhancement of foreign capital inflow by the liberalization of Chinese financial markets. Moreover, the investment portfolio of the CIC is characterized by several annual losses in series and by a large amount of illiquid investments including real estate, infrastructure, hedge funds and private equity which are not easy to quit (Gopalan 2019).