Kuanzhi 款識 [a special reading], also called zhikuan 識款, tikuan 題款, kuanshu 款署, kuanti 款題 or luokuan 落款, is a dated signature or a brief note of an artist of a calligraphy or painting. It usually includes the name of the artist (often just the courtesy name or style), and the date (season and cyclical characters of the day), and in some cases also a hint to the occasion when the artwork was produced, or include a kind of dedication.

The custom of adding the date began during the Song period 宋 (960-1279), while artists from the Yuan period 元 (1279-1368) onwards included shorter or longer prose or lyrical texts in their artworks, such as eulogies (huazan 畫贊), poems (tihua shi 題畫詩, tihua ci 題畫詞), notes (tihua ji 題畫記), "afterwords" (tihua ba 題畫跋), or other accompanying texts (huati 畫題). In early times, such texts written on paintings or beside calligraphic works often served an educational purpose. However, from the Song period onwards, the integration of kuanzhi texts into artworks reflected a combination of artistic and intellectual skills, namely painting, calligraphy, and poetry. It was thus an expression of cultured unity and identity. Notes, poems, and "prefaces" or "afterwords" (ti-ba 題跋) served several purposes: enhancing the overall impression of the artwork, extending the visual content into the mental and contemplative sphere, broadening artistic expression as a form of multiple beautification, and, ultimately, explaining a painting's meaning and message.

Scholars distinguish between various types of kuanzhi inscriptions, including dankuan 單款 (qiongkuan 窮款, mingkuan 名款) - the name or designation of the artist; shuangkuan 雙款 - the name of the recipient, as well as that of the calligrapher or painter; tishikuan 題詩款 - a poem (full or partial) related to the painting, either composed by the painter himself/herself or by a renowned poet from earlier times; tijikuan 題記款 - notes on the origin of the artwork, its significance, or related content; and jiahuakuan 夾畫款 - a special arrangement where additional text is inserted closely into the area of the painting or calligraphy, making it also visually part of the artwork.

The word kuanzhi was initially used for inscriptions on bronze vessels, as seen in Ruan Yuan's 阮元 (1764-1849) catalogue Jiguzhai zhongding yiqi kuanzhi 積古齋鐘鼎彝器款識. In this context, the term is first recorded in the imperial biography of Emperor Wu 漢武帝 (r. 141-87 BCE; 12 Xiao Wu benji 孝武本紀) in the history book Shiji 史記. Pei Yin’s 裴骃 (5th cent.) commentary clarifies that kuan meant "to carve" (kuan, ke ye 款,刻也), while Sima Zhen 司馬貞 (679-732) added that zhi meant "to express" (zhi, you biaoshi ye 識,猶表識). The phrase is also referenced in the chapter on state sacrifices (Jiaosi zhi 郊祀志) in the official dynastic history Hanshu 漢書.

Regarding the term kuanzhi, there are multiple interpretations. Pei Yin and scholars Wei Zhao 韋昭 (201-273) and Yan Shigu 顏師古 (581-645) suggest that kuan means "to carve," while zhi means "to record" (zhi, ji ye 識,記也). Kuan might also refer to incised characters (yinzi 陰字), and zhi to protruding shapes (yangzi 陽字). This view is presented in Tao Zongyi's 陶宗儀 (1322-1403) Chuogenglu 輟耕錄 (17 Gu tongqi 古銅器), which notes that incised characters marked ancient vessels, whereas protruding patterns appeared from the Han period 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE) onwards, indicating that they were typical of younger, non-antique vessels.

Alternatively, kuan referred to inscriptions inside, and zhi to those on the outer surface of objects. This interpretation is presented in Fang Yizhi's 方以智 (1579-1671) Tongya 通雅 (8 Qiyong 器用) as a quotation from the book Bogutu 博古圖. Fang also offers another explanation, namely that kuan could refer to patterns, while the word zhi denoted words or texts.

With the development of industrial production of porcelain, stamps were attached to the bottom of objects which referred to the place and time of production.

|

Painting of Monk Puhe 普荷 (1593-1683), style Dandang 擔當, from a four-leaf album with very inventive landscape paintings, Shanshui ce 山水冊. His own signature is Dan Laoren 擔老人 "Old Man Porter", inspired by the saying, "Even if a brush stroke counts as a painting, it is no painting; and if no brushstrokes counts as a painting, it is none as well." (有一筆是畫,也非畫;若無一筆是畫,亦非畫) From Xie Zhiliu 謝稚柳 et al., eds. (1986). A seal is imprinted (yinji 印記) as well.Zhongguo meishu quanji 中國美術全集, part Huihua bian 繪畫編, 9, Qingdai huihua 清代繪畫 (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe) Vol. 1, no. 13. |

|

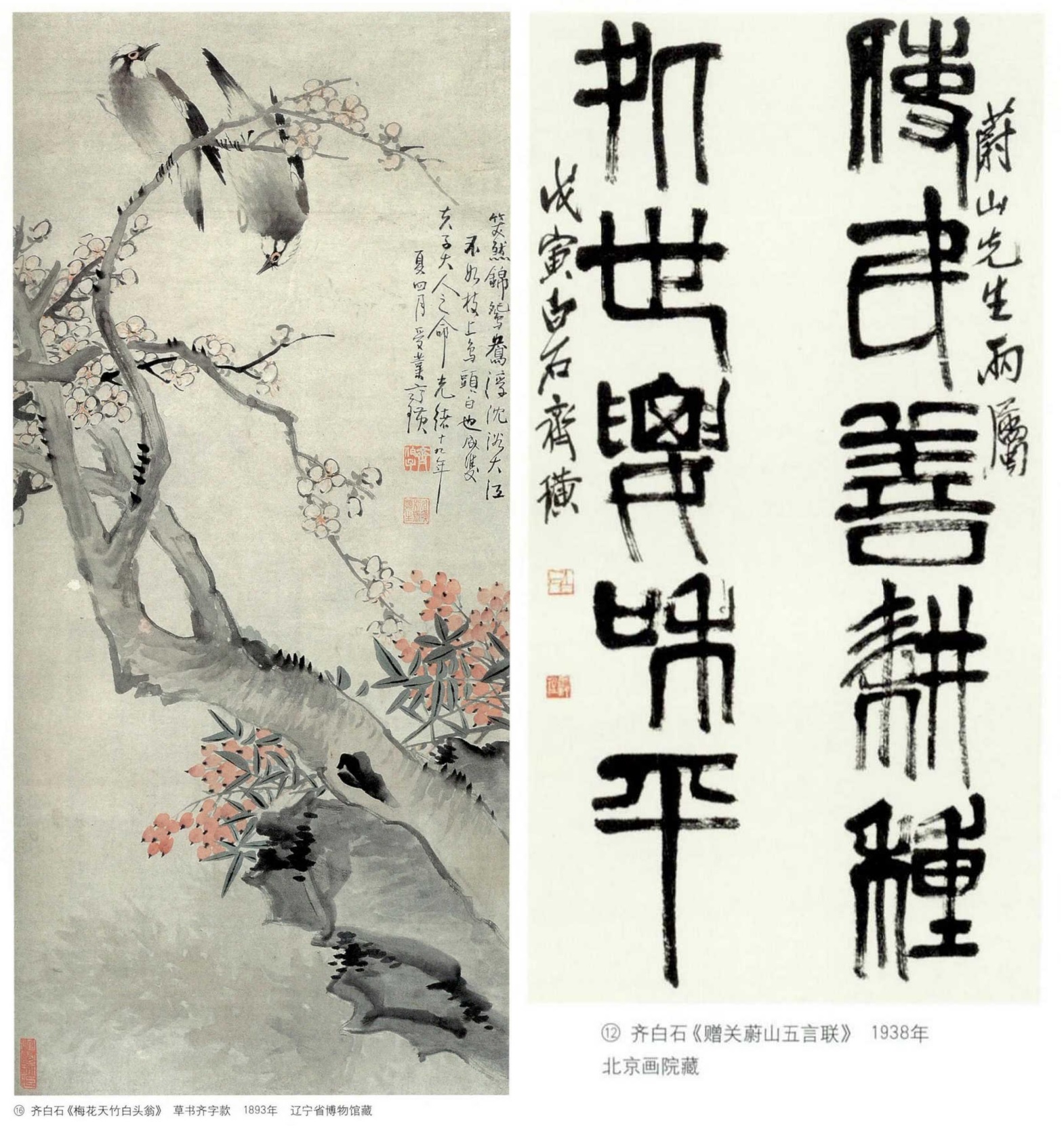

Kuanzhi notes with date, signature, poem and dedication on a painting (Meihua tianzhu baitouweng 梅花天竹白頭翁, 1893) and a calligraphy (Zeng Guan Weishan wuyan lian 贈關蔚山五言聯, 1938) of Qi Baishi 齊白石 (1864-1957), from Mou (2019). |