The Xia dynasty 夏 (21th - 17th cent. BCE) was, according to traditional historiography, the oldest of the Three Dynasties of antiquity (Sandai 三代: Xia, Shang 商 and Zhou 周). Yet unlike the two others, the authenticity of the Xia could never be surley established by archaeological findings.

Chinese scholars of the early twentieth century like Gu Jiegang 顧頡剛 (1892-1980) and Qian Xuantong 錢玄同 (1887-1939) doubted the historicity of the Shang and the Xia and called them inventions of mythology, like the stories about the Yellow Emperor 黃帝, Yao 堯, Shun 舜, or Yu the Great 大禹. Archaeological discoveries brought evidence about the historicity of the Shang dynasty. For the Xia dynasty, excavations in Erlitou 二里頭 near Zhengzhou 鄭州, Henan, have brought to light artefacts that might be remnants of a residence of the Xia, but so far no written source has been found that proves this identification. The state of the Xia was certainly not a territorial state ruling over large parts of China, as it is suggested in ancient histories, but it was only one of "ten thousand states" (wan guo 萬國) of what was later to become the cultural sphere of China.

According to traditional historical sources, the Xia dynasty was founded by Yu the Great (Da Yu 大禹), ennobled as Viscount of Xia 夏伯 by the mythological emperor Shun. Yu the Great is, like his father Gun 鯀, credited with the taming of the floods that inundanted the Central Plain. During his work, Yu the Great divided "China" into nine provinces (jiuzhou 九州). Each region had its particular rivers and mountains, and the soil was categorized into different classes of quality. Yu furthermore reported to the emperor which tributes each region or province was able to deliver. An account of these "Tributes of Yu" (Yugong 禹貢) are to be found in the Classic Shangshu 尚書 "Book of Documents", but this text was compiled as late as the the end of the Warring States period 戰國 (5th cent.-221 BCE) and is not an authentic report of the Xia period.

Yu, Bo Yi 伯夷 and Gao Yao 皋陶 served as the highest counsellors of Emperor Shun. When Shun died, Yu refused to succede to the imperial throne, as Shun had wished, and claimed that Shun's son Shang Jun 商均 might succeed, but the nobles all desired to serve Yu as the new emperor. Yu the Great is connected with the area of Guiji 會稽 (near Shaoxing 紹興 in modern Zhejiang) where tourists can still find his tomb.

Yu's son Qi 啟 was the first ruler in China who directly succeeded to his father. Before, all emperors had not chosen their own sons as successors, but a noble and worthy man. Under king (emperor) Tai Kang 太康 a rebellion of the king's five brothers (wuzi 五子) endangered the untiy of the kingdom. His brother and successor Zhong Kang 中康 was unable to control his ministers Xi 羲 and He 和 who engaged in lust and selfishness. During these years, the Lord of Yin 胤 attacked the two usurpers.

After several generations, King Kong Jia 孔甲 again endangered the royal line. The last ruler of Xia was Jie 桀, known as a cruel and depraved tyrant who was distracted from the business of politics by his consort Mo Xi 末喜. The lords of the various domains rebelled against Jie, their head being Tang the Perfect (Cheng Tang 成湯), who was incarcerated by Jie but later set free. The literary theme of a rebel who is first encarcated, then set free, and finally overthrows the ruling dynasty is repeated in the story of the last ruler of the Shang dynasty 商 (17th-11th cent. BCE). Tang assembled an army and dethroned Jie, who eventually died in exile in Nanchao 南巢 somewhere in the south. His descendants were made rulers of the small regional state of Qi 杞.

While the traditional accounts about the Xia dynasty were for a long time despised as pure mythiologcal accounts, the discovering of the inscribed oracle bones in Anyang 安陽, Hebei, had proved that the traditional ruler lists of the Shang dynasty provided in the history Shiji 史記 and the Zhushu jinian 竹書紀年 "Bamboo Annals" were not mythology, but historical fact.

|

|

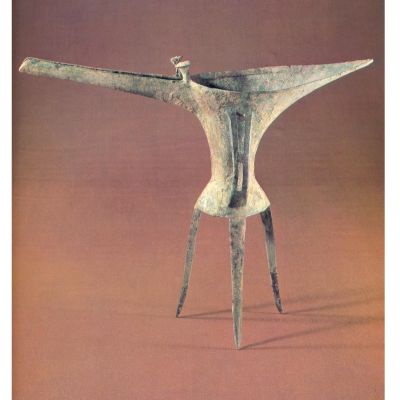

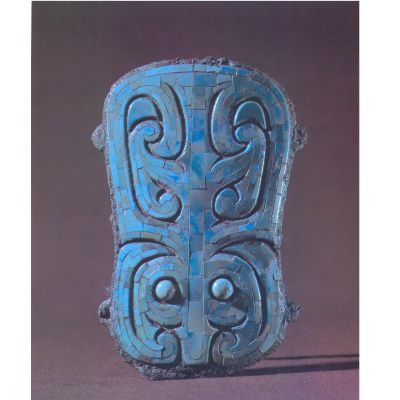

Left: Jue 爵-type tripod beaker unearthed in 1975 in Yanshi 偃師, Henan, one of the centers of Erlitou Culture. Height: 22.5cm. Right: Decorative object with turquois (lüsongshi 綠松石) inlay in the shape of a taotie 饕餮 pattern. Size: 14.2×9.8cm Unearthed in 1981 in Yanshi. From Zhongguo meishu quanji bianji weiyuanhui/Li (1985), nos. 2 and 3. |

|

Archaeology in the past seven decades or so has shown that the city of Yin 殷 as the last seat of the Shang dynasty was by no means a capital of a vast territorial kingdom, but rather one single city state (guo 國) that controlled other states and areas in a distance of several hundred miles. These states delivered tributes to the Shang court, and some places seem to have been colonies of the Shang with the purpose to ensure trade and ressources (see Shang society). It might have been a pure incidence that the Zhou-period historiographers chose the royal line of Yin/Shang as universal predecessor of their own dynasty. Similarly, the Zhou historiographers interpreted the royal line of the Xia as a universal dynasty controlling the Central Yellow River Plain before the takeover by the Shang. The real situation in the 15th to 14th centuries might have been quite different from these pictures in the traditional histories.

|

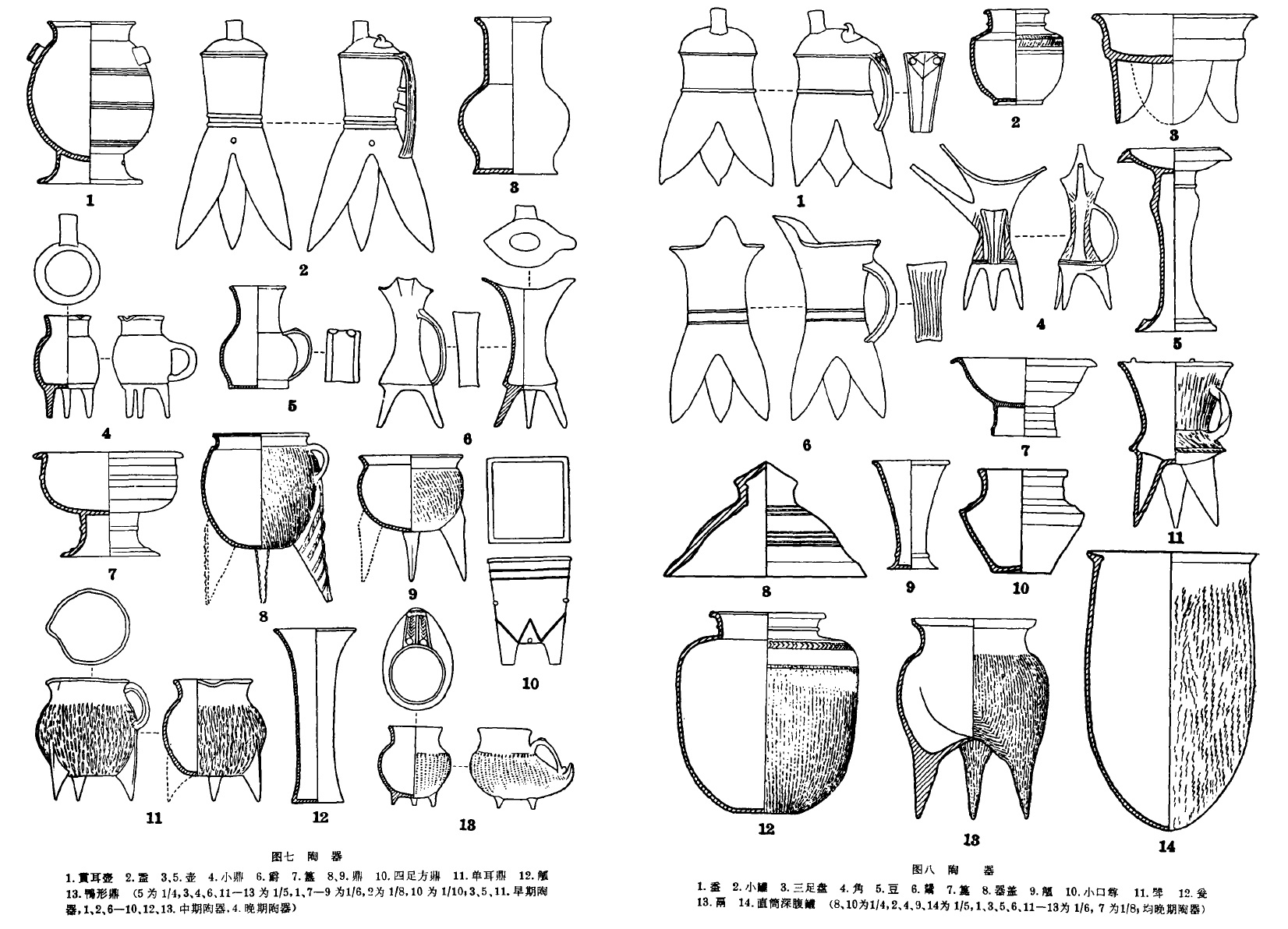

Various types of pottery unearthed in 1981 in Yanshi. From Zhongguo Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo Luoyang Fajuedui/Fang (1994). Click to enlarge. |

The mighty city state discovered in Erligang 二里岡 (modern Zhengzhou, Henan) controlled regions far south as Hubei and Jiangxi. Not far away, archaeologists discovered a neolithic and early bronze-age site near Erlitou that might well have been the domain of a royal house like that of Xia. Recently, pottery with signs interpreted as early forms of Chinese characters were discovered there.

The state of Erlitou was not only a cultural center whose inhabitants made use of a script, but archaeological remains that are linked with Erlitou (early Shang period) are dispersed in a large area of southern Shanxi and northern Henan. Erlitou might have been the mightiest state of a period before the first Shang polities rose to regional power. Probably later historians chose this state as predecessor of the later Shang Dynasty - that was likewise no single state but one of the most powerful of her time.

A dynasty called Xia could therefore have been masters over a mighty polity during the early Shang period or slightly before, and it was chosen by historians as a paradigm of that age because of its outstanding cultural achievements. Historiographers interpreted it as a universal dynasty. In this way, Xia could serve their model of China as a unified political entity. Still today, after many discoveries have been made, it is not yet clear which community might be identified with the seat of that Xia dynasty.

Some scholars locate a Xia polity in the east, in Shandong, while most scholars identify the Erlitou city with the Xia dynasty. The problem is even more difficult as the historical accounts speak of many transfers of the capital, and it is not clear whether the dynasties really transferred their capital because of unfavourable conditions in the surroundings, or if several cities were identified with the same royal line.