Chunhua fatie 淳化法帖, also known as Chunhuage fatie 淳化閣法帖, Chunhua bige fatie 淳化祕閣帖 (Chunhua mige fatie 淳化秘閣帖), Chunhuage tie 淳化閣帖 or Getie 閣帖 for short, is a collection of model calligraphies produced by Wang Zhu 王著 (c. 928-969) on imperial order of Emperor Taizong 宋太宗 (r. 976-997) of the Song dynasty 宋 (960-1279). Because it was a kind of "official" model, it is also occasionally known as Guantie 官帖.

Wang Zhu, courtesy name Ruwei 如微, was a recorder (zhubu 主薄) in the administration of Longping 隆平, and was later promoted to the position of court calligrapher in the office of the imperial clan (? taizong shishu 太宗侍書), and finally became palace censor (dianzhong shiyushi 殿中侍御史). Emperor Taizong had purchased countless ancient calligraphies that he wished to be copied on a less perishable material than paper or silk, and therefore ordered Wang Zhu, an experienced calligrapher, to reproduce the best calligraphies on wooden boards (tie 帖) and have it cut into stone, so that they could serve as model calligraphies (fatie 法帖).

The custom of incising famous calligraphic works into stone began during the Tang period 唐 (618-907). Collections of several artworks (as the Chunhuage tie was) were called huitie 彙帖, jitie 集帖 or congtie 叢帖. The oldest known collection was allegedly the Shengyuan tie 昇元帖, which was created in the empire of Southern Tang 南唐 (937-975) and was based on artworks in the collection of Xu Xuan 徐鉉 (916-991). This set, as well as the Baoda tie 保大帖 and the Chengxintang tie 澄心堂帖, are mentioned in historical sources, but it remains doubtful whether they really existed as collections of model calligraphies.

The calligraphic function of the model boards was just one aspect, while the contemporary function had also a political facet, namely the creation of a "complete" collection of calligraphic works by the imperial household with the attempt to monopolize the control over this realm of the arts, along with the question of standardization of "quality". The Chunhuage project must be seen in the context of the encylcopaedias Taiping guangji 太平廣記 (stories), Taiping yulan 太平御覽 (general knowledge) and Wenyuan yinghua 文苑英華 (literature).

|

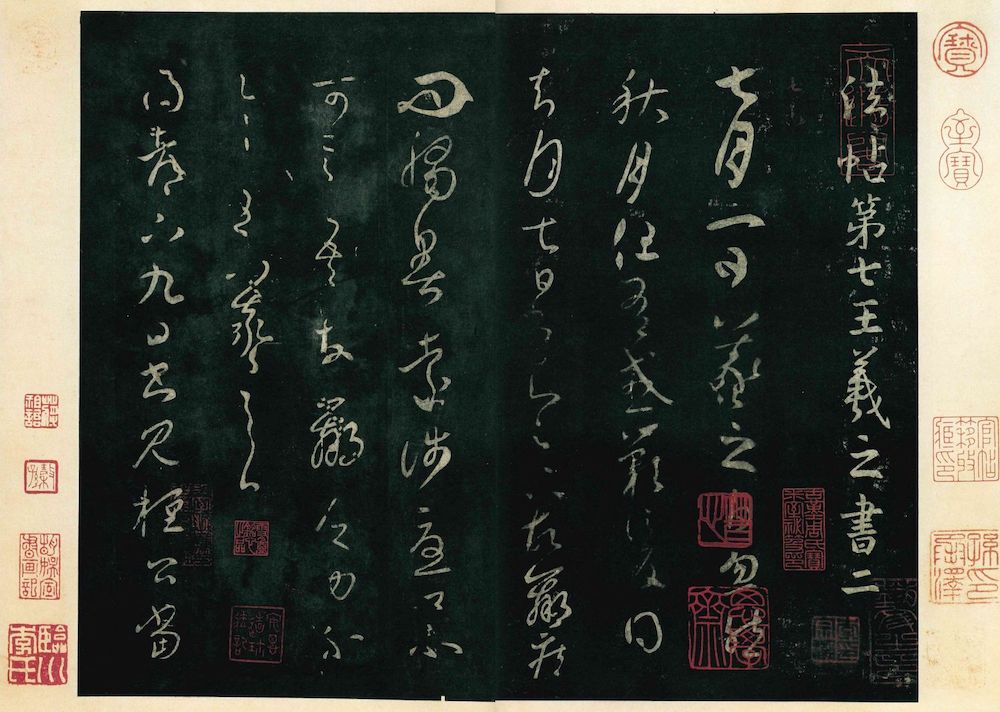

Beginning of Wang Xizhi's 王羲之 Qiyue tie 七月帖, juan 7, Wang Xizhi shu 2 王羲之書二. From Qi & Wang (2002), no. 132, which is a reproduction of the copy of Lu Cunzhen 麓邨珍, who reproduced the copy owned by Robert Hatfield. |

The model calligraphies carved into durable materials were created to be shown to the public, as a standard choice for imitation, much like the Stone Classics represented the imperially standard wording of the books of Confucianism. The originals of the model calligraphy boards were secluded in the collection in the Imperial Archives (Bige 祕閣 or Mige 秘閣) inaccessible to the public. Copies, however, were handed out as gifts to high officials and to princes who had achieved great merit.

Wang Zhu reproduced the most important model calligraphies in the shape of a 10-juan-long book encarved in boards of date wood (zaomu 棗木). The book Chunhua fatie included calligraphies from oldest times to the most famous Tang-period calligraphers, and also part of a Tang-period book on the calligraphies of the Jin period 晉 (265-420) master Wang Xizhi 王羲之 (303-361), the Hongwengguan tie 弘文館帖. Almost half of the book includes calligraphies of Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi 王獻之 (344-386). At the end of each fascicle, an afterword (wei 尾, ba 跋) was attached in seal-script style, referring to the date and the process of compilation.

The Chunhua fatie includes 2,287 standardized columns of calligraphic text, as well as a lot of detailed commentaries to the ancient masters' works. It served as a master for numerous of copies in later ages and was widely reproduced.

During the Southern Song period 南宋 (1127-1279), high officials began to publish copies of the Chunghuage fatie they had obtained, and thus contributed to the wide spread of the model calligraphies. Cao Shimian 曹士冕 (mid-13th cent.) says in his Fatie puxi 法帖譜系 that during his time, as many as 33 copies (fanke 翻刻) were circulating and until the end of the Song period, as much as 57. These publications were not all complete copies of the original, but selected individual calligraphic works (dantie 單帖), and enriched them with texts that had not been part of the original. In the course of time, a whole discipline emerged (tiexue 帖學) around the Chunhuage tie with copies, annotations, transcriptions, notes, and so on.

| Authenticity and errors | ||

|---|---|---|

| 跋祕閣法帖 | Ba bige fatie | (Song) 米芾 Mi Fu |

| 法帖刊誤 二卷 | Fatie kanwu | (Song) 黃伯思 Huang Bosi |

| 絳帖平 | Jiangtie ping | (Song) 姜夔 Jiang Kui |

| 法帖正誤 | Fatie zhengwu | (Yuan) 湯垕 Tang Hou |

| 淳化祕閣法帖考正 十二卷 | Chunhua bige fatie kaozheng | (Qing) 王澍 Wang Shu |

| Transcription and explanation of words | ||

| 法帖釋文 十卷 | Fatie shiwen | (Song) 劉次莊 Liu Cizhuang |

| 法帖釋文刊誤 一卷 | Fatie shiwen kanwu | (Song) 陳與義 Chen Yuyi |

| 法帖釋文考異 十卷 | Fatie shiwen kaoyi | (Ming) 顧從義 Gu Congyi |

| (欽定校正)淳化閣帖釋文 十卷 | (Qinding jiaozheng) Chunhuage tie shiwen | (Qing) QL 34 imp. ord. |

| (欽定重刻)淳化閣帖釋文 十卷 | (Qinding chongke) Chunhuage tie shiwen | (Qing) 于敏中 Yu Minzhong et al. (imp. ord.) |

| History of versions | ||

| 石刻鋪敘 | Shike buxu | (Song) 曾宏父 Zeng Hongfu |

| 法帖譜系 二卷 | Fatie puxi | (Song) 曹士冕 Cao Shimian |

| 寐叟題跋 | Meisou tiba | (Qing) 沈曾植 Shen Zengzhi |

| 淳化祕閣法帖考 | Chunhua bige fatie kao | (Rep) 容庚 Rong Geng |

| 淳化閣帖考 | Chunhuage tie kao | (Qing/Rep) 林志鈞 Lin Zhijun |

| 閱帖雜詠 | Yuetie zayong | (Qing/Rep) 張伯英 Zhang Boying |

The Chunhuage fatie includes 420 pieces of calligraphic artworks of 103 persons that are arranged in the following way: Fascicle 1 includes pieces produces by emperors and princes, juan 2-4 such of "famous ministers" (mingchen 名臣), juan 5 that of commoners and anonymous persons (zhujia 諸家), juan 6-8 calligraphies of Wang Xizhi, and juan 9-10 such created by Wang Xianzhi. The high appreciation of the two Wangs originated in the Tang period. Most artworks are written in the styles of "running script" (xingshu 行書) and "grass script" (caoshu 草書), but in the collection are also pieces in seal script (zhuanshu 篆書), chancery script (lishu 隸書), and standard script (kaishu 楷書). The calligraphies were incised (moke 摹刻, mole 摹勒) into wooden boards, but the project of having them cut into stone was apparently not realized. The rearrangement of the texts into columns of equal length led to some errors like double appearance of characters. Other errors of transfer from the "originals" to the model boards happened when characters were destroyed on the original, and the woodcarvers simply left them out instead of replacing the lacunae with the missing word. A third typical error was the inclusion of commenting words into the model. Other shortcomings of the model collection are abbreviated texts, wrong titles or names of artists, confuse chronological arrangement.

The oldest private reproduction of the Chunhuage tie was perhaps produced by Liu Hang 劉沆 (995-1060) in the 1040s, the so-called Tan tie 潭帖 or Changsha tie 長沙帖. Because it is lost, its quality and content cannot be verified. An enlarged version of 20 juan was produced in the 1050s by Pan Shidan 潘師旦, the so-called Jiang tie 絳帖 that was produced in Jiangzhou 絳州 (Shanxi). The oldest extant version that is fully based on the original is the so-called version of the Prince of Wei (Wei wangfu ben 魏王府本), of which juan 4 and 6-8 were owned by the US-American collector Robert Hatfield (1929-2014, Chinese name An Siyuan 安思遠). The Prince of Wei (posthumous title) was perhaps identical to Zhao Jun 趙頵 (1056-1088). His brother, Prince Zhao Hao 趙顥 (1050-1096), also produced copies of the original, a (lost) version called that of the "Second Prince" (Er wangfu ben 二王府本).

Another early version is that from Linjiang (Linjiang tie 臨江帖 or Xiyutang tie 戲魚堂帖) that was created in 1092 by Liu Cizhuang 劉次莊 (jinshi degree 1074), who reproduced the original copy of his family collection, eliminated the afterwords of each fascicle, and added remarks of his own. It was copied in the late 1190s by Quan An 權安 as the Lizhou tie 利州帖.

The version of the Directorate of Education from Shaoxing (Shaoxing Guozijian ben 紹興國子監本) from the Southern Song period, produced on imperial order, is quite probably lost. In 1185, during the Chunxi reign-period 淳熙 (1174-1189) the court had reproduced and enlarged the original to a size of 20 juan (consisting of Qiantie 前帖, and Xutie 續帖), but these "model boards produced at the court" (Chunxi xiunei tie 淳熙內修帖) are lost as well.

The Quanzhou version (Quanzhou ben 泉州本, Quantie 泉帖) or "horse-hoof" version (Mati ben 馬蹄本, according to a tale) is the most widespread version, with more than 40 different copies. Its origins are rather obscure. Shen Zengzhi 沈曾植 (1850-1922) found out that it was produced by Zhuang Zili 莊子禮 in Quanzhou according to a Northern-Song-period original, perhaps the Changsha version. Part of an original of the Quanzhou version, juan 9, is owned by the Shanghai Library (Shanghai Tushuguan 上海圖書館).

The most important Ming-period 明 (1368-1644) reproductions are the rare version of Yuan Jiong 袁褧 (Yuan Shangzhi 袁尚之, 1495-1573) which is based on a copy once owned by Jia Sidao 賈似道 (1213-1275); the version of Gu Congyi's 顧從義 (1523-1588) Yuhong Studio 玉泓館 from 1566 which is also based on Jia Sidao's original. Compared to Yuan Jiong's version that of Gu Congyi has one column more per page; the version of Pan Yunliang 潘允亮 (mid-late 16th cent.) and his Wushi Shanfang Studio 五石山房 from 1582 that also stands in the tradition of the two others; and the version of Prince Xian of Su 肅憲王 (Zhu Shenyao 朱紳堯, d. 1618; Su fu ben 肅府本, Su wangfu ben 肅王府本) from 1615-21, produced on the prince's order by Wen Ruyu 溫如玉 and Zhang Yinshao 張應召 as a stone inscription of the Zunxun Studio 遵訓閣. This version is also known as Lanzhou version (Lanzhou ben 蘭州本). It is based on a rubbing made by Zhu Yang 朱楧 (1376-1420), Prince Zhuang of Su 肅莊王, from the court copy of the Southern Song, and to a small part (juan 9-10) on the Quanzhou version. Apart from these high-quality reproductions, there was the version of Huang Jishui 黃姬水 (1509-1574), and a forgery known as Wang Zhu's version (Wang Zhu ben 王著本). The Qianlong Emperor 乾隆帝 (r. 1735-1796) ordered Yu Minzhong 于敏中 (1714-1779) in 1769 to rearrange the calligraphies more in a chronological way, a project which resulted in the version Qinding chongke Chunhuage tie (欽定重刻)淳化閣帖.