Pawnshops were enterprises where people pawned objects against money. The Chinese terms for pawnshops differed from time to time and from region to region. Common names were zhiku 質庫 (zhi 質 means "hostage" or "pawn"), zhisi 質肆, jieku 解庫, changshengku 長生庫, dianpu 典鋪, dangpu 當鋪, dangdian 當店, yadian 押店, yadangpu 押當鋪, xiaoya 小押 or diandang 典當. These various terms were also designations referring to the monetary volume offered against equivalent securities, with the order dian, dang, an 按, zhi, and ya, the first representing larger institutes, the last very small shops. The pawnshops handed over, together with the money, pawn tickets (dangpiao 當票), on which the redeemable pawn and the sum of money handed over were noted down. The term of validity ranged between six and eighteen months. Forfeits were called "dead pawns" (sidang 死當). Pawnshops earned a substantial interest from the difference between the pawn's value and the money lent. The calculation of this interest was normally made according to monthly rates, at an official rate of twenty to thirty per cent, yet in reality often much more. During the Qing period 清 (1644-1911) there were also public pawnshops run by the Imperial Household Department (neiwufu 內務府), called gongdian 公典 or gongdang 公當. The imperial minion Hešen 和珅 (1750-1799) is said to have run 75 pawnshops in the city.

The earliest proof for this type of monetary business dates from the Southern Dynasties period 南朝 (420~589), when monasteries used to run pawnshops. Individual officials, landowners or merchants also used to set up pawnshops as a kind of profitable investment. Pawned objects were not so much precious objects, but more often simple items of daily life, like clothes, or even grain. In dianpu shops it was even possible to pawn real property, at longer rates than in the dangpu shops. In the nineteenth century this difference was blurred.

|

|

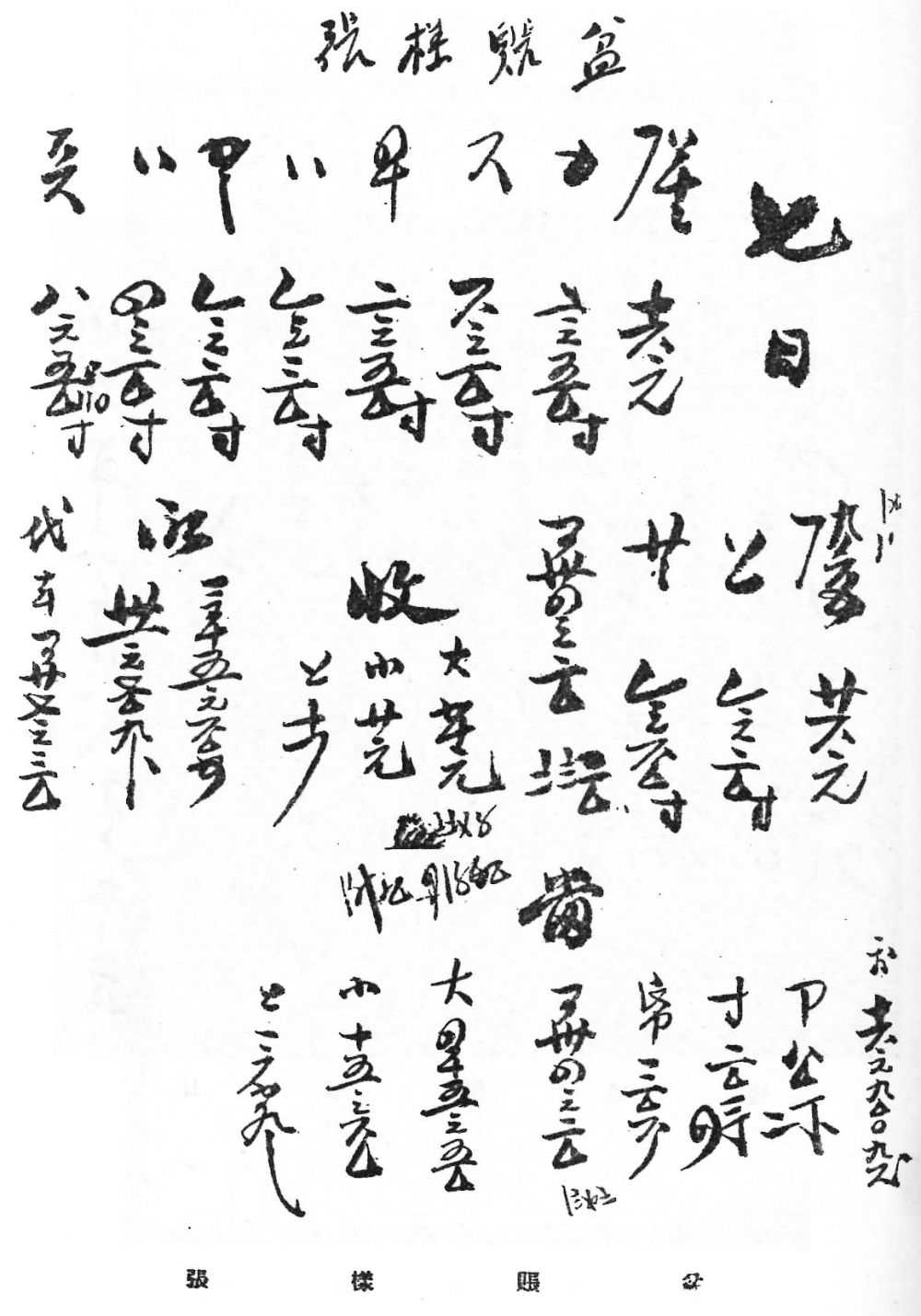

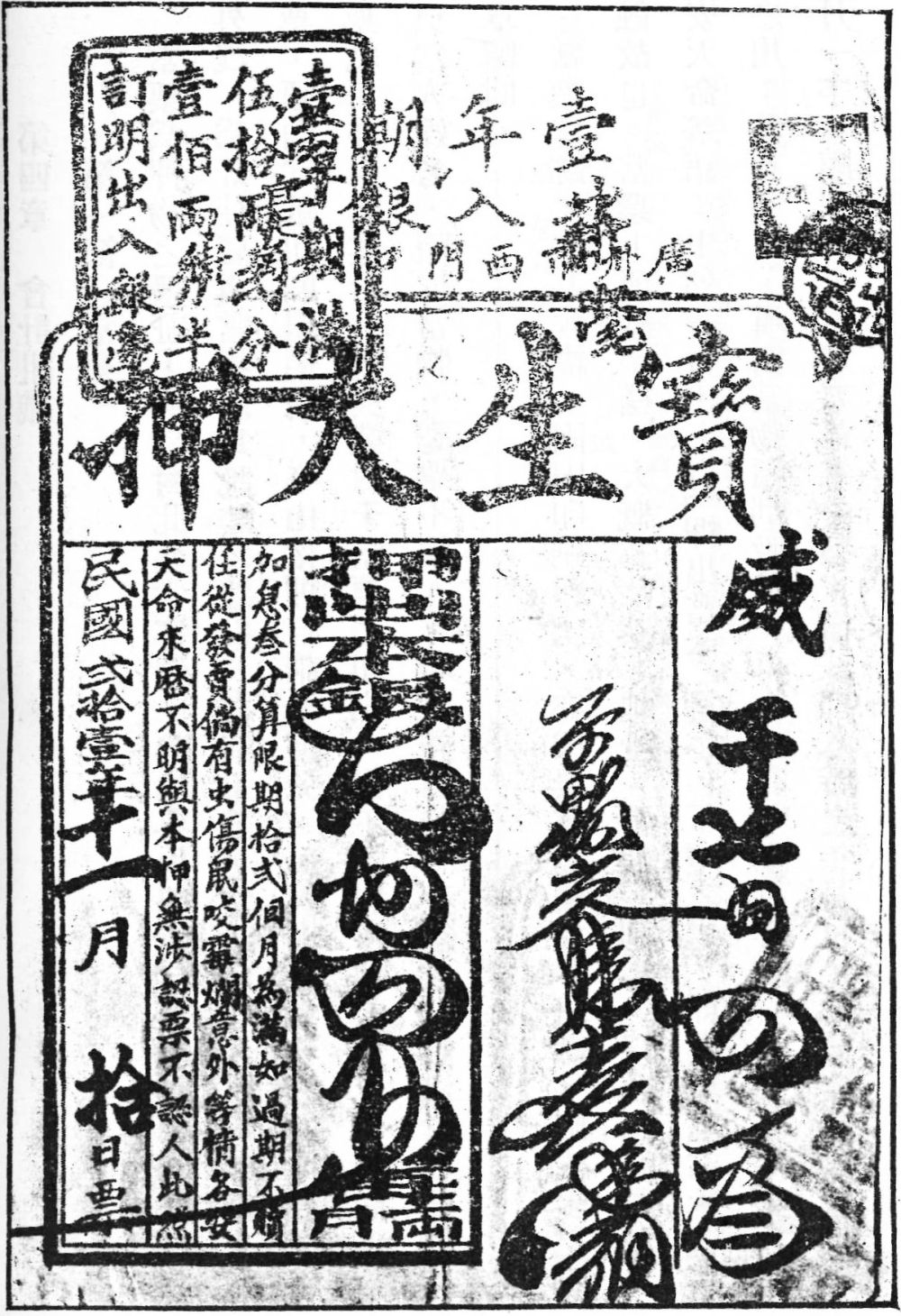

Left: Account book of a pawnshop recording the sizes of beacons and the pawn sums (pen zhang yangzhang 盆賬樣張). From Mi 1936. Receipt of a pawnshop in Guangzhou. The sheet is printed, but the entries written by hand. It can be seen that pawnshops used a particular writing style which is not easy to read. Books on the history of pawnshops therefore offer transcriptions of documents. From Qu 1934. |

|

During the early Qing period there were more than 20,000 registered pawnshops in the empire, and in the mid-18th century, 600 to 700 in Beijing, yet in 1888, there were more than 7,000 in the capital. This number demonstrates that before the introduction of modern banking, pawnshops often served as credit institutes. Roger Greatrex (2015) has described that pawnshops also served as a “money laundering” places for petty thieves.

The government levied a tax on pawnshops (called dangshui 當稅 or tiejuan 帖捐). Institues in smaller towns were called daidang 代當, daisui 代歲 or jiedian 接典, branch agencies also bendai 本代, and if operating for other institutions, kedai 客代. The larger pawnshops were allowed to issue bank notes for silver tael and copper cash, causing the operative capital (jiaben 架本) to surpass the sum of cash-in-hand.