The Grand Canal or Imperial Canal, in Chinese Nanbei da yunhe 南北大運河, Jing-Hang da yunhe 京杭大運河, Da yunhe 大運河, or short Yunhe 運河, was a canal system along which tribute grain was transported (see tribute grain transport) from the Lower Yangtze region (with the southern terminal at Hangzhou 杭州, Zhejiang) to the imperial capital, in earlier ages Chang'an 長安 (today's Xi'an 西安, Shaanxi) or Luoyang 洛陽 (today in Henan), later on Beijing. The Grand Canal was probably the longest canal system on earth (measuring 1,794 km) and is in parts still used today. It had presursors during the late Spring and Autumn period 春秋 (770-5th cent. BCE). In its classical shape, the Grand Canal was built by the Sui dynasty 隋 (581-618).

This gigantic system of canals linked the most important economical zones of China with the capital city/cities and some border garrisons in the northeast and would be in use for the following 600 years in this shape. It thus not only supplied the capital and sensitive border areas with grain, but also contributed to the reconstruction of the economy after centuries of turmoil. The Yuan dynasty 元 (1279-1368), residing in Beijing in the far north, rebuilt the northern parts of this canal system. In 1283 the Jizhou Canal 濟州河 and the Huitong Canal 會通河 were built that crossed the Shandong Peninsula.

In 1291 the Tonghui Canal 通惠河 was opened, rich in sluices and dams, and linking Tongzhou 通州 with Dadu. During the Ming 明 (1368-1644) and Qing 清 (1644-1911) periods the Canal was several times obstructed by silt because at that time the Yellow River flew south of the Shandong Peninsula, through the bed of River Huai 淮水 (until 1855), and laid down huge deposits of loess in the riverbed. The New Nanyang Canal 南陽新河 was therefore built as well as the Dongyun Canal 東運河 which helped avoiding the passage through the Yellow River.

The oldest canalisation projects were carried out during the Spring and Autumn period 春秋 (770-5th cent. BCE), especially by the southern states of Chu 楚 and Wu 吳.

Around 600 BCE the king of Chu had the Jiang-Han Canal 江漢運河 created, also called Yang Cangal 揚水 or Zixu Channel 子胥瀆. This was a canal running parallel to River Ju 沮水 (another name for River Han 漢水), beginning in the place of modern Qianjiang 潛江, Hubei, and entering the Yangtze close to the capital of Chu, Ying 郢 (modern Jiangling 江陵, Hubei). King Ling 楚靈王 (r. 541-529 BCE) created another canal north of modern Jianli 監利, Hubei, and King Zhao 楚昭王 (r. 516-489 BCE) extended this waterway.

The Ancient Jiangnan Canal 古江南河, created around 500 BCE, sprang off Lake Taihu 太湖 at Wudu Pingmen 吳都平門 (close to modern Suzhou 蘇州, Jiangsu) and crossed Lake Chao 巢湖 (today called Lake Caohu 漕湖), touched Meiting 梅亭 (near Wuxi 無錫, Jiangsu), crossed Lake Yang 楊湖, the Yu Creek 漁浦 and the Yangtze River and extended northwards to Guangling 廣陵 (near Yangzhou, Jiangsu). South of this canal, the "Hundred Ells Channel" Baichi 百尺瀆 linked the capital of Wu with the Qiantang River 錢塘江. These canals were the forerunners of the Jiangnan Canal 江南運河.

North of the Yangtze River, the Han Canal 邗溝 was created in 486. It began in Hancheng 邗城 or Guangling and crossed Lake Wuguang 武廣 (today Lake Shaobo 邵伯湖), Lake Luyang 陸陽 (today Gaoyou 高郵, Jiangsu) and Lake Fanliang 樊梁湖 (today Lake Gaoyou 高郵湖) and ran northwards through the lakes Bozhi 博芝湖 and Sheyang 射陽湖 (near modern Baoying 寶應, Jiangsu) and finally entered River Huai. It was the precursor of later canals, too, and extensively used natural water reservoirs.

Yet more northwards was the He Canal 菏水 or Shen Canal 深溝, created in 484 BCE, which used the waters of the He Swamp 菏澤 and entered River Si 泗水. Today, a canal system running along this line is called the Wanfu Canal 萬福河. It was a short, but important link between the Yangtze River and tributaries of the Yellow River.

Some states located close to the Yellow River built canals, too, like Wei 魏 that in 361 BCE connected the fields around the capital Daliang 大梁 (today's Kaifeng 開封, Henan) with the waters of the Yellow River through the Hong Canal 鴻溝. This canal reached further on eastwards to the state of Chen 陳 (today's Huaiyang 淮陽, Henan) and connected the Yellow River with the hydrological systems of the southeast. It was thus possible to reach the Rivers Sui 睢水, Ying 潁水, Ru 汝水 and Guo 渦水 south of the Yellow River Plain. It was the longest canal sytem of the pre-Qin period.

The most important canal of the Qin period 秦 (221-206 BCE) was the famous Lingqu Canal 靈渠 that connected the two river systems of the Yangtze (in particular that of River Xiang 湘水, running through the modern province of Hunan) and the "Pearl River" Zhujiang 珠江 (River Li 漓水) and made it possible to transport commodities from central China to the south. This canal is still in use today. It is located near Xing'an 興安, Guangxi.

Another hydrological project of the Qin dynasty was the Dantu Canal 丹徒水道 in the Lower Yangtze region that extended the Ancient Jiangnan Canal from today's Zhenjiang and Danyang 丹陽 to the region of the commandery of Guiji 會稽 (at that time identical to modern Suzhou, Jiangsu). Another section led from Chongde 崇德 (today's Chongfu 崇福鎮) southwest to the banks of the Qiantang River at Hangzhou, Zhejiang.

During the Han period 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE) the large dimensions of the capitals Chang'an and Luoyang required a better system for supplying the population and the officialdom with tribute grain. In addition to that, Emperor Wu 漢武帝 (r. 141-87 BCE) undertook several military campaigns in which large troops had to be fed. The many shallows and meanders of River Wei 渭水 made it a difficult water to bring grain to Chang'an. Emperor Wu therefore in 129 BCE ordered to build a the Grain Canal of Guanzhong 關中漕渠 that run parallel to River Wei. Along this 300 li- 里 (see weights and measures) long canal, an amount of 4 million shi 石 (see weights and measures) of grain could be transported each year.

The Hong Canal east of Luoyang was also widened and supplemented with the Langdang 蒗蕩渠 (also spelled Langtang 狼湯渠) and the Junyi Canal 浚儀渠. The Hong Canal began at Xingyang 滎陽 (today's Zhengzhou 鄭州, Henan) in the commandery of Henan 河南, fed by the waters of the Yellow River, and was diverted into two branches. The southern branch, the Langdang Canal, led southwards to River Ying, a tributary to the Huai River. The eastern branch of the Hong Canal run eastwards from Chenliu 陳留 to Yangxia 陽夏 (today's Taikang 太康, Henan) and into River Guo. Part of its waters were diverted and formed the Bian Canal 汴渠 (the river supplementing the canal is spelled 汴水 or 汳水). This region was several times inundated by the floods of the Yellow River. In 69 therefore Wang Jing 王景 carried out changes in the canal system. From Junyi 浚儀 (modern Kaifeng 開封, Henan) the water of the Langdang Canal was diverted more northwards to Xuzhou 徐州, where it entered River Si. This was the Junyi Canal that was at that time the most important arteria connecting the Yellow River Plain with the Huai River region.

Another project from the early Later Han period was the Yangqu Canal 陽渠 that tamed the waters of the River Luo 雒水 (later written 洛水) around the Eastern Capital, integrated the waters of the creeks Gu 谷水 and Chan 瀍水, and reentered the Luo at Yanshi 偃師 more eastwards. It joined the waters around Luoyang with River Ji 濟水 and thus secured the supply of tribute grain to the Eastern Capital from the Shandong Peninsula.

In the southeast, the Han Canal was still used and regularly reconditioned. Liu Pi 劉濞, the Prince of Wu 吳, had a new section constructed in the southern parts of the Han Canal that was the precursor of the modern Tong-Yang Canal 通揚運河.

When the central government of the Later Han 後漢 (25-220 CE) disintegrated, the warlord Cao Cao 曹操 (155-220) took over the governmental duty to secure transport channels. He organized the construction of six canals that began in 202 CE, namely the Suiyang Canal 睢陽渠 (a northward extension of the Hong Canal and a canalization of River Sui until Suiyang 睢陽, today's Shangqiu 商丘, Henan), which had a critical function for supplying Cao Cao's troops before the decisive battle of Guandu 官渡 against Yuan Shao 袁紹 (d. 202); the "White Canal" Baigou 白溝 (also called Suxu Channel 宿胥瀆) that led the waters of River Qi 淇水 into the Bai Canal leading northwards, and so supplying Cao's residence in Ye 鄴 (modern Linzhang 臨漳, Hebei); the Pinglu Canal 平虜渠 for "the suppression of the barbarians" (as a linkage of the rivers Zhang 漳河, Hutuo 滹沱河 and Hu 泒河 with River Lu 潞河 in the north); the Quanzhou Canal 泉州渠 (close to modern Tianjin, as a northward extension of the Pinglu Canal); the "New Canal" (Xinhe 新河) towards the east (to River Ru 濡水) along which grain was shipped to feed the troops campaigning at he rivers Ju 泃河 and Baoqiu 鮑丘水 against the steppe federation of the Wuhuan 烏桓 in the northeast; and finally the Licao Canal 利漕渠, a junction of the White Canal and River Zhang. Cao Cao's construction activities in northern China were crucial for the economic situation of the empire that was eventually founded by his son.

Cao Pi 曹丕 (187-226), Emperor of the Wei dynasty 曹魏 (220-265), relied on four residences, namely the capital Luoyang, as well as Xuchang 許昌 (today in Henan), Qiao 譙 (today's Boxian 亳縣, Anhui), Ye and Chang'an. Of particular interest for Emperor Wen 魏文帝 (r. 220-226), under which name Cao Pi is known, was the supply of the troops campaigning against the empire of Wu 吳 (222-280) in the southeast. He had therefore the canal system in this region widened and the "Military Canal" (Taolu qu 討虜渠) built which linked the Rivers Ru and Ying, and the Jiahou Canal 賈侯渠 that joined the Rivers You 洧 and Ru. In 238 the Lukou Canal 魯口渠 and the "White Horse" Baima Canal 白馬渠 were opened, linking the waters of River Zhang in the northeast with that of the Hutuo and Gu rivers. In 243 the southern river system was joined anew by the Guanghuaiyang Canal 廣淮陽渠 and the Baichi Canal 百尺渠.

War remained one motive for canal construction in the following centuries. In the far southeast, Sun Quan 孫權 (182-252), Emperor of Wu, founded the capital of his empire in Jianye 建業 (modern Nanjing, Jiangsu), and connected this city with the water system of the region of Lake Taihu. In 245 he had a large number of military agro-colonies (tuntian 屯田) founded whose troops dug the Pogang Channel 破崗瀆 between what is today Suzhou and Shaoxing 紹興, Zhejiang. It was wide enough to carry war ships between the capital and the Hangzhou Bay. It was equipped with sluices in the stetch of the Shangrong Channel 上容瀆 during the Liang period 梁 (502-557) to be navigable even in winter. The Jurong Midland Canal 句容中道 led the water from the Taihu region directly to Jianye, and made it easier to ship grain to the capital without relying on the Yangtze River. Sun Quan had also refurbished the Dantu Canal between Zhenjiang and Danyang.

The Jin dynasty 晉 (265-420) also took care of this waterway to transport grain from the Lake Taihu northwards. The Zhedong Canal 浙東運河 was a waterway between the Rivers Qiantang and Yao 姚江 whose origins went back to canalization projects of Goujian 句踐 (r. 495- 465), King of Yue 越, during the Spring and Autumn period. It was rebuilt during the Western Jin period 西晉 (265-316) and reached from Guiji (today's Shaoxing, Zhejiang) to River Cao'e 曹娥江 eastwards. The city of Jiangdu (today's Yangzhou) became an important trade hub and was linked with the west through the Ouyang Canal 歐陽埭 and the Zhong Channel 中瀆. This was the precursor of the Zheng-Yang Canal 征揚運河 that still exists today.

When in 369 the Eastern-Jin 東晉 (317-420) general Huan Wen 桓溫 (312-373) planned his campaign against the statelet of Former Yan 前燕 (337-370) he envisaged to have his troops carried on River Si to the north, and therefore ordered Mao Muzhi 毛穆之 to enhance the canal system of this region. The Wen River 汶水 was connected with River He (He Canal) in the south and the Juye Swamp 巨野澤 in the north. This hydraulic system, called "Duke Huan" Huangong Canal 桓公溝, connected the rivers Si, Wen and Ji, and in effect opened the way to the Yellow River and the west. In 416 and 430 Liu Yu 劉裕 (363-422), founder of the Liu-Song dynasty 劉宋 (420-479), and general Dao Yanzhi 到彥之 (d. 433) made use of this system for their military campaigns against the northern empires.

In the middle Yangtze region the hydrological system of the Yangkou Canal 揚口運河 was built in what is today the province of Hubei. Its origins were during the Qin period, when the lower course of River Han was made navigable and even reached back to the Jiang-Han Canal from the Spring and Autum period. Du Yu 杜預 (222-284) was during the early Western Jin period responsible for a general reconstruction of this system. It made it possible to ship goods from Jingzhou 荊州 (modern Jiangling 江陵, Hubei) up the Han River, and also downwards into the southern regions.

Most of the capitals of Chinese dynasties were located in the north, either in the region "within the passes" (Guanzhong 關中, Guannei 關內), like Chang'an, in the Yellow River area (the "Central Plain" Zhongyuan 中原), like Luoyang or Kaifeng, or far in the north, like Beijing. All these capitals were located in an environment where agricultural production was not sufficiently high to support the need of a metropolis with a million inhabitants. This problem had aggravated during the period of division, when the agriculture of northern China was in shambles, while that in the southeast began to flourish.

To supply troops in the conquest of the Chen empire 陳 (557-589) in the south in 587, the Sui dynasty 隋 (581-618) had the Shanyang Canal 山陽瀆 created which linked Shanyang 山陽 (today's Huai'an 淮安, Jiangsu) with the Sheyang Lake and the old Han Canal in the southeast. This waterway made a comfortable passage between the Huai River and the Yangtze River possible.

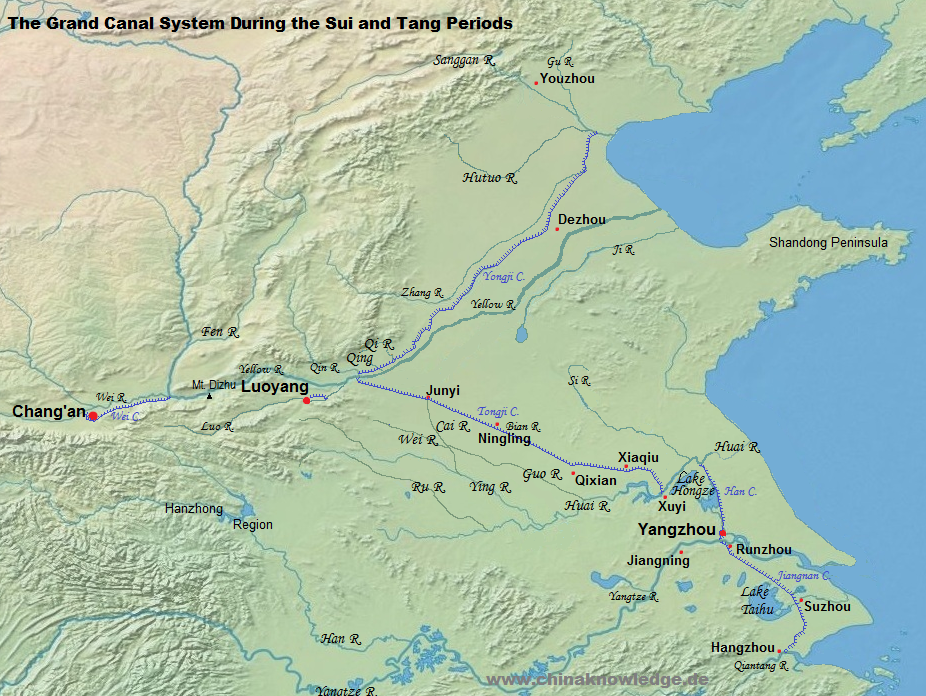

In 605 Emperor Yang 隋煬帝 (r. 604-617) decided to found a second seat of government, the Eastern Capital (Dongjing 東京, i.e. Luoyang), which also had to be supplied by canals. An insurmountable number of peasants, both men and women, were therefore recruited (see corvée) to link the commandery of Henan 河南 with the Huai River region by the Tongji Canal 通濟渠. This canal used the waters of the Rivers Gu and Luo and used the ancient course of the Hanyang Canal 漢陽渠. At Yanshi the Canal entered the River Luo, and boats so reached the Yellow River. The eastern part of the Tongji Canal began at Banchu 板渚 (close to modern Yingyang, Henan), using the waters of the Yellow River, and entered River Bian up to Junyi (i.e. Kaifeng 開封, Henan). From there it went southeast to pass Chenliu, Yongqiu 雍丘 (Qixian 杞縣, Henan), Xiangyi 襄邑 (Suixian 睢縣, Henan), Ningling 寧陵 and Songcheng 宋城 (today Shangqiu, Henan). From this town it entered the ancient course of River Qi 蘄水 and passed Gucheng 谷熟 (Yucheng 虞城, Hunan), Zanxian 酂縣 (Xiayi 夏邑, Henan), Yongcheng 永城, Qixian 蘄縣 (Suzhou 宿州, Anhui), Xiaqiu 夏丘 (Sixian 泗縣, Anhui) and Xucheng 徐城 (today Xibaoji 西鮑集 at the banks of Lake Hongze 洪澤湖 in Jiangsu) and reached the banks of River Huai in Xuyi 盱眙. In the same year the ancient Han Canal was repaired to replace the Shanyang Canal used during the Han period and later. Both waterways, the Tongji and the Han Canal, had a width of 40 paces (bu 步) and thus allowed a large fleet to ship from the Eastern Capital in Luoyang to the Yangtze Capital (Jiangdu) in Yangzhou.

In 608 another part of the canal system was begun. This was the Yongji Canal 永濟渠 which used the waters of River Qin 沁水 as a link to the Yellow River in the south. In the lower reaches of River Qin links were dug out by corvée labourers to the rivers Qing 清水 and Qi 淇水 and the Bai Canal 白溝. The canalized River Qing connected the Yellow River with Dezhou 德州 (today's Lingcheng 陵城, Shandong) and further on to where today Tianjin is located. From there, the waters of River Gu 沽水 (today Baihe 白河) and River Sanggan 桑乾水 (today called River Yongding 永定河) allowed river transport to Zhuojun 涿郡. The canal system towards the north was important for the military campaign in 611 against the kingdom of Koryŏ 高麗 on the Korean Peninsula. It was possible to reach the hinterland of the war theatre from the Yangtze Capital along the Han Canal, the Tongji Canal, the Yellow River, and the Yongji Canal to Zhuojun, from where the troops were supplied.

In order to make inspection tours in the southeast, particularly to Guiji, more comfortable, Emperor Yang had also built a navigable river system between Jingkou 京口 (today's Zhenjiang, Jiangsu) at the Yangtze to Yuhang 余杭 (i.e. Hangzhou). It was based on earlier canals from the Southern Dynasties period, but widened the canals to a width of more than 10 zhang 丈, so that the imparial barges ("dragon boats" longchuan 龍舟) could pass them. Yet in the end, Emperor Yang never carried out an inspection tour to Guiji.

The banks of the Sui canals were equipped with an inspection road (yudao 御道), protected by alleys of willows. Along the whole canal between Chang'an and Jiangdu, more than fourty so-called "palaces on leave" (ligong 離宮) were built, and of course a large number of granaries, where the grain was reloaded in a relay system. The most important of these granaries were the Liyang Granary 黎陽倉 (close to modern Junxian 浚縣, Henan), the Xingluo Granary 興洛倉 close to Luoyang (later called Luokou Granary 洛口倉, in today's Gongxian 鞏縣, Henan; it actually consisted of a wide system of cellar granaries in the surroundings), the Huiluo Granary 迴洛倉 near Luoyang (also written 回洛倉, and likewise consisting of a system of cellar storerooms), the Hanjia Granary 含嘉倉 (also close to Luoyang), the Heyang Granary 河陽倉 (close to modern Mengxian 孟縣, Henan), the metropolitan Ever-Normal Granary (Changpingcang 常平倉; it lend its name to the regular granary system) in Shaanxian 陜縣 (close to the Sanmen Gorge 三門峽), the Guangtong Granary 廣通倉 in Huayin 華陰 (later called Yongfeng Granary 永豐倉; located where the River Wei enters the Yellow River), the Grand Granary (taicang 太倉) in Chang'an and the Shanyang Granary 山陽倉 (in today's Huai'an, Jiangsu). These granaries did not only serve to supply the capitals with grain, but also the surroundings in times of famine.

The network of canals during the Sui period reached from Daxing 大興 (i.e. Chang'an) in the west and linked the commandery of Zhuojun in the northeast (today's Bejing) and Yuhang in the southeast, and thus connected the systems of Dagu River (today's River Haihe) with that of the Yellow River, the River Huai, the Yangtze River and the Qiantang River (in modern Zhejiang). All important cities of the empire could be reached by this canal system: The metropolitan area (Jingshi 京師, i.e. Chang'an), the Eastern Capital (Luoyang), Zhuojun (Youzhou 幽州), Junyi (Bianzhou 汴州, i.e. Kaifeng), Liangjun 梁郡 (Songzhou 宋州, today Shangqiu, Henan), Shanyang 山陽 (Chuzhou 楚州, today Huai'an, Jiangsu), the "Yangtze Capital" Jiangdu (Yangzhou), Wudu 吳郡 (Suzhou) and Yuhang (Hangzhou). This system was an important component for the eventual revival of a nationwide economy under the Tang dynasty.

Each canal section was called caoqu 漕渠 or caohe 漕河 throughout the Sui and Tang periods. The eastern part of the Tongji Canal 通濟渠 was known as Bian Canal, the Han Canal and the Jiangnan Canal 江南河 were known as "Official Canal" (Guanhe 官河). The Yongji Canal was still called by this traditional name, but already disconnected with River Qin 沁水, and instead using the waters of River Qing 清水 and River Qi 淇水. The most important part of the canal system was of course the linkage between Chang'an, Luoyang, and the Huai River Region.

|

During the reign of the Emperors Gaozu 唐高祖 (r. 618-626) and Taizong 唐太宗 (r. 626-649) of the Tang dynasty 唐 (618-907) an amount of 200,000 shi of grain was shipped to Chang'an every year. The demand for rice increased drastically under Emperor Gaozong 唐高宗 (r. 649-683), and the volume was raised to 2.5 million shi. The long-term supply of the western capital Chang'an with rice was a difficult project. Most critical was the passage through the Three Gorges, where many boats capsized. The canal in the Guanzhong region was soon abandoned, and boats moved up the River Wei to bring heir loads to the capital. Between Luoyang and the west, therefore, land transport was chosen as a less difficult mode of transport. The eastern parts of the Grand Canal were often impassable because of silt blockage. Another problem was the different height of water levels of the many rivers integrated into the canal system. Sluices were still scarce, and the waterlevels of the separate and widespread river systems frequently differed from each other.

During the reign of Emperor Xuanzong 唐玄宗 (r. 712-755), Pei Yaoqing 裴耀卿 (681-744) suggested to create a new waterway to bypass the Three Gorges to shorten the way on which grain was transported by land. A relay granary was built at the spot, where River Bian sheds its waters into the Yellow River. The boats bringing in grain from the Huai River region were emptied and then returned. From there, other, government-hired boats brought the rice to a granary east of Mt. Sanmen 三門山, from where it was transported by land to another granary in the west of the mountain, and from there by boat again to the granaries in the metropolitan region of Guanzhong. Yet still, transport was only possible when the waterlevel in the rivers was high enough. In 734 this plan was adopted, and the Heyin Granary 河陰倉 was built (close to modern Yingyang, Henan), and the Jijin Granary 集津倉 and the "Salt Granary" (Yancang 鹽倉) east and west of Mt. Sanmen. North of that mountain, a road was built. The grain arriving at the Heyin Granary was shipped to the Hanjia Granary in Luoyang, or to the Taiyuan Granary 太原倉 (the former Changping Granary), and from there to the Yongfeng Granary 永豐倉 (the former Guangtong Granary), the Weinan Granary 渭南倉, and finally to the Grand Granary in Chang'an. Pei Yaoqing was appointed transport commissioner (zhuanyunshi 轉運使) for Jiang-Huai 江淮 and Henan 河南. Under his supervision an amount of 7 million shi of grain was brought to Chang'an in the following three years, and the cost for land transport was reduced by 400,000 strings of cash.

The stretch of road transport around Mt. Sanmen was finally replaced in 742 by the Sanmen Canal 三門運渠, also called "New Canal of the Kaiyuan reign-period" (Kaiyuan xinhe 開元新河) or Tianbao Canal 天寶河. In case of flood, haulers (chenfu 纖夫) helped the boats river up, yet a landslide made use of this canal impossible. In 742 transport commissioner (shuilu yunshi 水陸運使) Wei Jian 韋堅 (d. 746) had a new canal built from Xianyang 咸陽 to Chang'an, using the waters of River Wei and blocking the rivers Ba 灞水 and Chan 滻水. East of Chang'an, boats were tied in the Guangyun Reservoir 廣運潭.

The rebellion of An Lushan 安祿山 (703-757) in the mid-8th century broke the economic link between the southeast and the capital. The regions of the northeast, with large granaries in Weizhou 魏州 (today's Daming 大名, Hebei) and Beizhou 貝州 (today's Qinghe 清河, Hebei), known as the "northern storehouses of the empire" (tianxia beiku 天下北庫), brought only minor relief. Grain and the commodities and money levied in the lower Yangtze area were therefore shipped up the River Yangtze and River Han 漢水. The route through the mountainous region of Hanzhong 漢中 was very costly and difficult, and therefore the normal route was used as soon as the rebellion was ended. Unfortunately the River Bian and its canals were thoroughly silted and impassable. The palace in Chang'an had to live from the grain produced in the Guanzhong region.

In 764 transport commissioner Liu Yan 劉晏 (716-780) suggested a new transport mode. The government would build 2,000 boats, each able to carry 1,000 shi of grain. Ten boats were a "flotilla", with a team of 300 men and 50 punters (gaogong 篙工). Where needed, boatmen from the salt flotilla were hired, but no private persons. Between Yangzhou and the Huaiyin Granary, troops were responsible for the grain transport, and from then on, the boats were hauled. The transport commissioners and their team were to see to it that experienced boatmen were used for each part of the canal system, to have a most efficient way of transport. For the same reasons, boats from Yangzhou only went as far as Heyin, while boats on the River Bian did not transport the grain along the Yellow River, and so on. Weikou 渭口 was the endpoint for boats operating on the Yellow River, while yet a different flotilla brought the grain from Weikou to the capital. This system drastically cut expenses and increased the transport volumes considerably. As the result, a volume of 1.1 million shi were exported from the Jiang-Huai area to the north; 400,000 shi were stored in the Heyin Granary, 300,000 in the Taicang Granary, and 400,000 arrived in Chang'an.

The second half of the Tang period saw frequent insurgencies by military commissioners (fanzhen 藩鎮). The rebellion of Li Xilie 李希烈 in 786, for instance, cut the arteria of the Grand Canal for four years. The lower Yangtze region had by that time become the breadbasket of China control over which secured the life of the dynasty. The numerous uprisings in the last decades of the Tang period again brought a deadlock to the canal transport, and the Five Dynasties 五代 (907-960) reigning northern China in the first half of the ninth century had to do without it. Only in 955 the Later Zhou dynasty 後周 (951-960) took care for the repair of the old canal system as a part of their conquest projects towards the Southern Tang empire 南唐 (937-975). These measures were the beginning of the revival of the system under the Song dynasty.

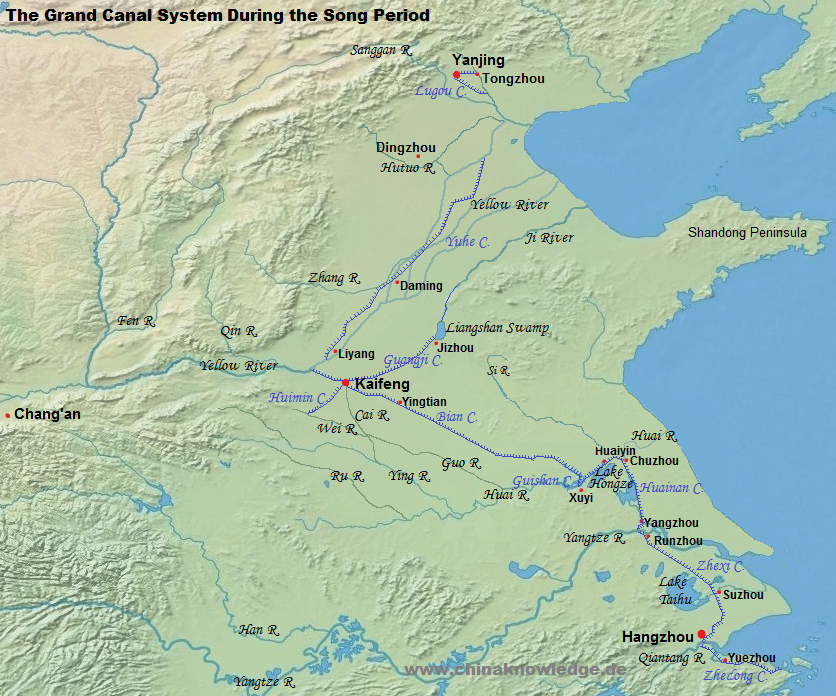

The Song dynasty took Kaifeng as the seat of the central government, and so solved all problems of the western branch of the Grand Canal system. Chang'an fell into oblivion, and changed into a military camp for the defence of the western border towards the empire of the Western Xia 西夏 (1038-1227).

From Kaifeng, a canal still led to the west, entering the Yellow River at Biankou 汴口 in the district of Heyin 河陰 (close to modern Yingyang, Henan). To the east, the Bianhe Canal reached to Sizhou 泗州 (today's Xuyi, Jiangsu, at the southern shore of Lake Hongze), where it joined the River Huai. The commodification and monetization of the economy during the Song period, along with an increasing urbanization, relied to a substantial part on the system of the Grand Canal. In its northern parts, it was endangered by the floodings and the silt-rich waters of the Yellow River. A series of measures was therefore necessary to retain the quality of the canal sytem. One was the regulation of the water exchange at Biankou, where the River Bian flows into the Yellow River, with the help of a sluice. For this task, a special official was appointed who commanded a staff of local labourers. This "task force" consumed huge amounts of funds, but was important to keep off the water of the Yellow River from the canals. In 961 the waters of the rivers Suo 索水 and Xu 須水 were diverted into the River Bian, and in 1079 a water engineering project forced the Rivers Luo and Qing 清水 into the River Bian. The water of these rivers was not only much less loaden with silt than that of the Yellow River, but could also be led into reservoirs (pitang 陂塘) keeping back superfluous water. From time to time the River Bian was freed from silt deposits.

In 1056 the width of the Bian Canal between Kaifeng and Yingtian 應天 (Songcheng, modern Shangqiu) was narrowed with the help of wooden banks, in order to increase the velocity of the water and help clearing away the silt. Troops were commandeered to fix the dykes along the canal and to plant trees alongside. In addition to that, sluices helped regulating the flow of water. Water level indicators made of stone were erected at the Yellow River. All these measures helped to increase the transport volume of rice brought to the capital. It reached its peak in 1008 with 7 million shi of grain. The transport system followed a mode of "network transport" (gangyun 綱運) with flotillas of ten to thirty boats. The silt deposits continued to present a danger for the canal transport system. In the late decades of the Northern Song period, the water level of the canals, and not only that of the Yellow River, was already one zhang higher than the surrounding landscape. The western parts of the system were abandoned when the Jurchens conquered northern China.

|

Another branch of the canal system was the Huimin Canal 惠民河 that incorporated the rivers Min 閔水 and Cai 蔡河. The work at this canal was begun in 961. It began at the River Wei 洧水 south of Xinzheng 新鄭 and reached the outskirts of Kaifeng. The Rivers Wei and Yi 潩水 led to the southeast, where they reached River Ying. Towards the west, this canal system allowed easy transport to the prefectures of Xuzhou 許州 and Ruzhou 汝州. In order to reach the water system of the Xiang 襄 and the Han farther to the southwest, the Fangcheng Canal 方城運河 project was initiated, but it failed because the engineering challenges were too high. At least, the River Ru was joined to the system of the Huimin Canal. The latter was important as it integrated the economy of the prefectures southwest of the capital to that of the metropolitan region. An annual amount of 600,000 shi of grain came from there, as well as huge amounts of tax money and commodities like salt, tea, and firewood. While the Bian Canal silted up in in mid-12th century, this system remained intact and was an important part in the economy of the Jin and the early Yuan period.

The canal branch to the northwest, called Guangji Canal 廣濟河 or Canal "Five-Paces [Wide]" (Wuzhanghe 五丈河), was an important arteria between Kaifeng and the Shandong Peninsula. In the early years of the Song period it was equipped with roads to make hauling easier. It left Kaifeng to the east and touched Jizhou 濟州 and Caizhen 蔡鎮 (today's Yuncheng 鄆城, Shandong), where it entered the Liangshan Swamp 梁山泊 and then River Ji. It served for the transport of up to 700,000 shi of grain and other products from the east to the capital. The Wuzhang Canal was supplied with water of the Jinshui Canal 金水河, which itself came from west of Kaifeng and was fed by the rivers Jing 京水 and Suo. It water was very clear and therefore also used as drinking water for the capital and to fill the streams and lakes in the imperial park. Several changes in the course of the Yellow River devastated the region, so that the eastern parts of the Wuzhang/Guangji Canal were abandoned around 1100.

North of the Yellow River, the "Imperial Canal" (Yuhe 御河) inherited the function of the old Yongji Canal. It was mainly used to supply the garrions in the border region to the Liao Empire 遼 (907-1125). They obtained grain from the southeast that was shipped across the Yellow River and then to Liyang 黎陽 (today’s Junxian 浚縣, Henan), where the Yuhe began. It touched Daming with the Jisheng Granary 濟勝倉 and went on to the rivers Hulu 胡盧河 and Hutuo, and on to the northeast to the New Canal of Shenzhou 深州新河 and the New Canal of Jiashan 嘉山新渠 in the prefecture of Dingzhou 定州, and on to the individual garrisons. After 1048 the Yellow River changed its course several times over wide distances, which made it impossible to maintain the canal system of the Yuhe.

The Huainan Canal 淮南運河 (consisting of the Han Canal and the Shanyang Canal) was likewise widened and renovated. Its northern parts connected Chuzhou (today's Huai'an, Jiangsu) with Huaiyin 淮陰, and from there crossed the Hongze Lake as the Hongze Canal 洪澤渠. At its southern banks, the transport route went through the new, short Guishan Canal 龜山運河 close to Xuyi, and from there via the Bian Canal to the capital. This way was much more comfortable than the route from Chuzhou northwards used before.

The stretch between Hangzhou and the Yangtze River, formerly called Jiangnan Canal 江南河, now Zhexi Canal 浙西運河, was equipped with sluices and roads for hauling the boats. South of Runzhou 潤州 (today’s Zhenjiang, Jiangsu), the Jingkou Sluice 京口閘 was located. New canals in that area helped to control the influx of water from the Yangtze and its tributary rivers.

In 1126 the Jurchens, founder of the Jin empire 金 (1115-1234), conquered the remainders of the Liao Empire in north China and occupied the capital city of the Song, Kaifeng. The court fled to the southeast, where they re-founded the Song dynasty in the prefecture of Lin'an 臨安 (Hangzhou). The Southern Song had lost a substantial part of territory in the north, but the new capital was located very close to the empire's breadbasket and in a water-rich area where boat transport was common and easy. The southern parts of the Grand Canal, reaching from the Huai River region (now the border zone to the Jin empire) to the estuary of the Qiantang River and beyond, remained intact and were used intensively. These parts were called Huainan Canal 淮南運河, Zhexi Canal, and Zhedong Canal 浙東運河. The latter, a new water engineering project of the Southern Song, started in Xixing 西興鎮 in the district of Xiaoshan 蕭山, crossed Yuezhou 越州 (Shaoxing) and Shangyu 上虞, and was in Mingba 明壩 connected to the transport network of the rivers Wangjiang 浣江 (today called Puyang 浦陽江), Cao'e 曹娥江, Yuyao 余姚江 and Dajia 大浹江 (today called Yongjiang 甬江), and reached the East China Sea at Dinghai 定海 (today's Zhenhai 鎮海, Zhejiang).

The Zhedong Canal was always preferred to the sea route, and used to transport commodities from southern China, the overseas countries in the South China Sea, and even envoys from foreign countries. It thus also served as an instrument of administration and politics of the Southern Song court. The old canal between Zhenjiang and Lin'an was widened and equipped with sluices of up-to-date technology. In the north, the remainder of the Grand Canal of course also served to ship supplies to the border garrisons at Chuzhou (today's Huai'an, Jiangsu).

The "central" capital (Zhongdu 中都) of the Jin empire was Yanjing 燕京 (today's Beijing) and was supplied by the grain from the Shandong Peninsula and what is today the province of Hebei. When the Jurchens conquered northern China, the Yellow River had changed its course to the south and devastated the Bian Canal and the Guangji Canal. The Huimin Canal and the Yuhe Canal were intact and served the grain transport system of the Jin, but only after large-scale reparation works under the emperors Shizong 金世宗 (r. 1161-1189) and Zhangzong 金章宗 (r. 1189-1208). The functioning of these canals was also important to bring troops to the border to the Southern Song empire.

The Yongji Canal was out of use. In 1171 therefore the Lugou Canal 盧溝河 was created that reached the capital city from the southwest, and the "Sluice Canal" (Yahe 閘河) that linked Tongzhou 通州 at the River Lu 潞水 with Yanjing. Yet this system was imperfect because the territory was relatively high, and the rivers of the region carried too much silt. Overland transport was therefore part of the system. Only in 1204 the canal system between the Yuhe and the capital was finished, with the result that grain boats could reach Yanjing. More to the south, parts of River Qin 沁水 were in 1216 transformed into a navigable waterway joining the Yuhe Canal. The transport system was also perfected by that time. Grain was stored along the canal in granaries, and flotillas (gangchuan 綱船) were organized that shipped the grain twice a year, when the water levels were favourable. Northeast of Yanjing a short canal was built as a connection to the Wenyu River 溫榆河 (today called Ba River 壩河). Minor reconstruction projects were carried out in the southern regions to make transport along the rivers Bian and Si possible. Most important is the canal system around Yanjing that later served the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties for their canal transport systems.

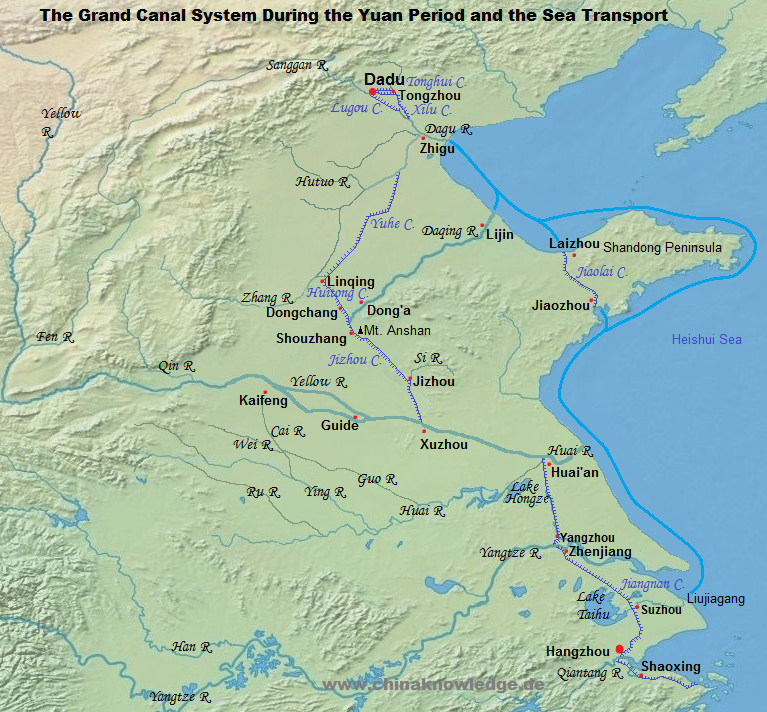

The Mongols inherited the central capital of the Jurchens and renamed it Dadu 大都 (modern Beijing). They supplied their capital with grain from the Shandong Peninsula and southeast China, and for this purpose changed the canal system that had been used by the Tang and the Northern Song.

The Grand Canal of the Yuan was more than 3,000 li-long and consisted of several parts. The Tonghui Canal 通惠河 connected Dadu with Tongzhou 通州 in the east, where the grain arrived either through the Dagu River 大沽河 (today called Haihe River 海河) from the sea, or through the Yuhe Canal 御河 (today called Weihe 衛河) running northwards across the lower Yellow River plain. It must be said that since 1128 the Yellow River run south of the Shandong Peninsula and several times changed its course. From about 1330 it shed its waters into the Huai River, entering the sea in what is today the northern part of the province of Jiangsu. The Yuhe Canal reached Linqing 臨清, from where a new canal was dug out through the Shandong Peninsula. This was the Huitong Canal 會通河, ending at the banks of the Daqing River 大清河 (modern lower course of the Yellow River), and the Jizhou Canal 濟州河, ending in Jizhou, where the canal integrated the River Si and led down to Xuzhou, at that time located at the Yellow River. Between Xuzhou and Huai'an, the Yellow River was part of the Grand Canal. The parts of the canal south of River Huai were intact and continued to serve for the transport of tribute grain.

The greatest problem for the transport to the north was that the ships had to be hauled up part of the Yellow River until Zhongluanhan 中灤旱 (near today's Fengqiu 封丘, Henan), from where the grain was transported overland for 180 li to Qimen 淇門 (near modern Junxian, Henan), where the Yuhe began.

The engineering project of the Jizhou and the Huitong canals was quite novel. The waterway crossed high territory with a peak point in the region of Mt. Anshan 安山. Work at the Jizhou Canal began in 1276. In the coming seven years a 150-li long canal was constructed between Jizhou (today's Jining 濟寧, Shandong) to Mt. Anshan close to Xucheng 須城 (today's Dongping 東平, Shandong). Grain boats coming from the south left River Huai and entered River Si (today called Zhongyun Canal 中運河; later on the Yellow River shifted its bed into that of River Si), and from Xuzhou on the Grand Canal. Towards the north, the Jizhou Canal entered River Daqing, which crossed Dong'a 東阿 (today in Shandong) and Lijin 利津 (today in Hebei), before shedding its waters into the sea. During the time of sea transport, ships went along the Bohai Sea and regained land at Zhigu 直沽 (today's Dagukou 大沽口, Tianjian), from where the grain was brought to the capital Dadu. The Qinghe Canal soon silted up, so that overland transport was necessary from Dong'a to Linqing, where the Yuhe Canal began.

After 1287 the tribute grain administration began direct sea transport from the lower Yangtze region which greatly supported the transport along the Grand Canal. The Huitong Canal project was begun in 1288, as a realization of a proposal presented in a memorial by Han Zhonghui 韓仲暉. Li Chuxun 李處巽 was entrusted with the management of the project. The new canal began at Anshan and crossed the Liangshan Swamp 梁山濼, ran along Shouzhang 壽張 and Dongchang 東昌 (today's Liaocheng 聊城) and joined the Yu Canal at Linqing. The 250-li long waterway was finished within just six months of work. It included no less than 31 sluices and locks. The canal was located in an area where earlier the Yellow River had been, and was therefore dubbed the "Northern Yellow River" (Bei Huanghe 北黃河).

|

Another, smaller hydrological project was the Tonghui Canal. In 1261 Guo Shoujing 郭守敬 (1231-1316) had submitted a proposal to connect the capital (at that time of the Jin empire) with Tongzhou and with Yangcun 楊村 (today's Wuqing 武清, Tianjin). The project was not carried out, but the Yuan administration had great interest in ameliorating the water transport around the capital, in spite of lacking water resources. Guo Shoujing therefore submitted his proposals a second time, this time with concrete proposals how to use the local water courses and reservoirs. After two failed attempts, a canal of 164 li of length was constructed between Dadu and Tongzhou in 1291, integrating 21 sluices. From Tongzhou to the southeast, another waterway was created, running along the ancient course of River Lu, and therefore called Xilu Canal 西潞河 or White Canal (Baihe). It reached River Dagu in the south, but did not carry sufficient volumes of water. In the far south, the Han Canal close to Yangzhou had silted up in the last decades of the 13th century. Successful dredging work was only carried out in 1317. The Jiangnan Canal 江南運河 (during the Song called Zhexi Canal) was also dredged in the early 1320s, and also widened and deepened. Its northern parts, close to Danyang, called Zhenjiang Canal 鎮江運河, were changed somewhat to use the waters of the small Lianhu Lake 練湖.

The Yuan administration cared a lot for the smooth administration of the transport of tribute grain. High officials were entrusted with the duty to oversee the Grand Canal along its new course through the Shandong Peninsula, but also for the sea transport.

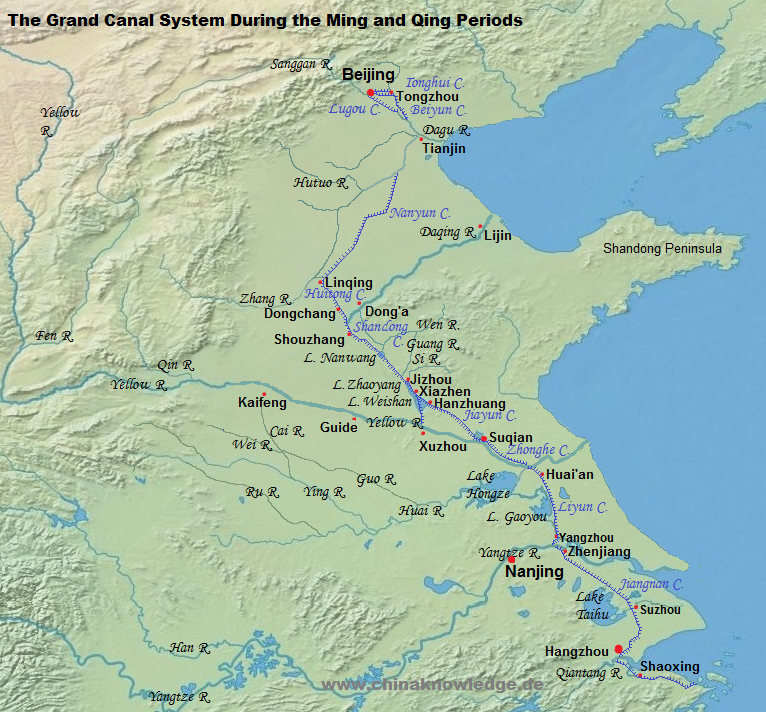

In the first decades of the Ming period, the imperial capital was in Nanjing, a city very close to the "granary" of China. Yet Emperor Chengzu 明成祖 (r. 1402-1424) chose Beijing as his seat of government, while Nanjing remained secondary capital. The Grand Canal that had been built by the Yuan dynasty crossed relatively high territory on the Shandong Peninsula. This stretch was only to be crossed with great difficulties, partly because sluices were necessary, and partly because the water level was often not high enough because the region was quite dry. Emperor Chengzu therefore sent out Chen Xuan 陳瑄 (1365-1433) to inspect the canal connection between the south and the north. Minister of Works (gongbu shangshu 工部尚書) Song Li 宋禮 (1358-1422) was entrusted with the task to dredge the Huitong Canal and the Jizhou Canal. A certain Bai Ying 白英, a local expert, gave advice to the imperial commissioners.

The Ming dynasty modernized the canals of the Yuan, built new sluices on the Tonghui Canal between Beijing and Tongzhou, and renewed the water reservoirs feeding the Huitong Canal across the Shandong Peninsula. 51 new sluices regulated the water level on this way. Between Jizhou and Xuzhou, a series of lakes was created to supply the water of the Grand Canal after leaving the Yellow River towards the north. After some engineering works between 1528 and 1605 the canal in this area deviated from the Yuan period canal and run across Xiazhen 夏鎮, Hanzhuang 韓莊 and Tai'erzhuang 臺兒莊, joining the Yellow River at Peixian 邳縣. This was the Hanzhuang Canal 韓莊運河. This waterway remained the arteria until the beginning of the Qing period.

|

The Qing administration did not only use the canal systems that had been created by the earlier dynasties, but also used natural water courses for the transport of tribute grain. While the ancient canals were still used by the Qing, they were given different names inspired by the grain transport system. In its grain transport function the Tonghui Canal between Beijing and Tongzhou was thus called Licao Canal 里漕河, and the way between Tongzhou and Tianjin (Beiyunhe 北運河, Baihe 白河, Luhe 路河 or Waihe 外河) was called Baicao 白漕, Lucao 路漕 or Waicao Canal 外漕河. The Southern Transport Canal (Nanyunhe 南運河) between Tianjin and Linqing (also known as Weihe Canal or Yuhe Canal) was given the name Weicao 衛漕. The Huitong Canal between Linqing and Tai'erzhuang 臺兒莊 (close to Hanzhuang), also known as the Shandong Canal 山東運河, was called "Sluice Transport Canal" (Zhacao 閘漕) because it was equipped with more than fourty sluices and locks.

Between Tai'erzhuang and Huaiyin (Huai'an) the Yellow River was used for grain transport, and the stretch accordingly called Hecao 河漕. The Liyun Canal 里運河 between Huaiyin and Yangzhou was also called Huai-Yang Canal 淮揚運河, South Canal 南河 or Gao-Bao Canal 高寶運河. The parts leading through the lakes Baoying 寶應湖, Gaoyou 高郵湖 and Shaobo 邵伯湖 were called Hucao 湖漕. The southernmost part between Zhenjiang and Hangzhou was called Jiangnan Canal or "Grain Transport" Canal (Zhuanyun he 轉運河). The two stretches north and south of Suzhou had special designations, namely Dantu Canal or Jiangcao canal 江漕 for the northern part, and Zhejiang Canal 浙江運河 or Zhecao Canal 浙漕 for the southern part.

River work was during the Qing period carried out in mainly two spots, namely the Huitong Canal in the western parts of the Shandong Peninsula, and in the northern parts of the province of Jiangsu, between the Yellow and the Yangtze River. The Huitong Canal led through high territory that was relatively dry. Two problems had therefore to be solved, namely the balance of the water level, and the supply of enough water. In the early Qing period, the Huitong Canal had already silted up, and the natural lakes close to Anshan, Nanwang 南旺, Mata 馬踏 and Weishan 微山 had fallen dry or were consumed to feed the local irrigation projects of the peasantry. The Qing therefore took some drastic measures to reconstruct the canal. New dams were built with reservoirs, the canal was widened and dredged, the banks were consolidated, and more water sources made useable. All lakes in the region were incorporated into the water system of the canal, and new reservoirs built. Water reservoirs were protected by trees, and not accessible to the local peasantry. Offenders were punished harshly.

The waters of the River Wen were dammed with the Ticheng Dam 堤城壩 (close to modern Ningyang 寧陽, Shandong) and diverted into the River Wen proper, which fed the Daqing River in the north, and the River Guang 洸水, which directly supplied the Huitong Canal. Another source was River Si, dammed up with the Jinkou Dam 金口堰 (near today's Yanzhou 兖州), and also flowing into two directions, once north, and feeding the Canal together with River Huang at Jining (Jizhou), and once southwards, entering the Canal at a series of sluices.

Most critical was the northern end of the Liyun Canal at Huai'an, where the Yellow River flew into the old bed of the Huai River. Because the Liyun Canal crossed several lakes, it did not follow a straight line, but rather a crisscross path. In case of floods in the bed of the Yellow River, there was the greatest danger that the whole system might break at that point. In the 1650s the floods of the Yellow River even chose the way south, flew through Lake Hongze and entered the Yangtze River. The transport system of the Grand Canal was disrupted. Intensive river works in 1676 forced the Yellow River back into the bed of the Huai River. In 1677 Jin Fu 靳輔 (1633-1692) was appointed Director-General of the Grand Canal (hedao zongdu 河道總督) and suggested to renew the whole system of dams to prevent similar occurrences in the future.

While the dams of the Yellow River and the Huai were rebuilt and reinforced, the Grand Canal through the many lakes was dredged and widened and its banks strengthend. Lake Hongze and several other waters of the region were used as reservoirs. They would be able to store superfluous water, and their dams could be opened to flush the riverbeds to wash away silt deposits. In addition to that, locks were built in 34 points to regulate the water level of the Canal, and 26 sluices and 54 reservoirs crated. The work at the two rivers and the Canal were finished in 1683, and the passage made safe again for more than a century.

Yet the passage up the Yellow River remained a dangerous enterprise. As soon as 1602 the authorities had the Jiayun Canal 泇運河 opened, beginning in Xiazhen 夏鎮 (toda's Weishan 微山, Shandong), passing Tai'erzhuang, and ending in Suqian 宿遷. In 1688 this bypass was further worked on. The Qing had a canal built running parallel to the Yellow River, the so-called Zhonghe Canal 中河 (also called Zhongyun Canal 中運河) with a length of 180 li. The Zhonghe Canal was secured by double sluices. Transport boats left the South Canal at Qingkou 清口, crossed the Yellow River to its north bank, and entered the Zhonghe Canal at Zhongjiazhuang 仲家莊 by the Shuangjin Sluice 雙金閘. Close to Zaohe 皂河 it left the Yellow River and went northwards. The northern half of the Zhonghe Canal was somewhat later shifted to the north. This "New Midland Canal" (Xinzhonghe 新中河) had stronger dams than the former one. Zhang Pengge 張鵬翮 (1649-1725) as Director-General again modernized these two canals and so created a reliable canal, with the beginning at Zhangjiazhuang 張家莊.

In the late 18th century intensive work at the Yellow River and the Grand Canal became very urgent. The River several times flooded the surrounding country, and the Canal silted up because of the many loess carried by the Yellow River. Yet the management of the Grand Canal was very careless and shied away from investing money in large-scale repair work for dredging the canal beds and restrengthening the banks and dams.

The situation became much worse during the Jiaqing reign-period 嘉慶 (1796-1820), and in many years the Grand Canal was just impassable. For this reason, a new sea transport project was brought into life, by which the tribute grain was directly shipped from Shanghai along the coast to Dagu, where it was reloaded to be brought to Beijing on lighters. To make things worse, in 1855 the Yellow River broke its dams at Tongwaxiang 銅瓦廂, Henan, and returned back to north of the Shandong Peninsula, where it had run before the Song period. At that time, the parts of the Grand Canal between River Huai and the Yangtze River (the Jiang-Huai Canal) were silted up and unuseable.

Parts of it were reconstructed, but just for local use. The reconstruction works were carried out in the 1950s and allowed a regular transport of 20 million tons of goods annually between Xuzhou and the Yangtze River. Apart from serving as a means of transport, the canal system was also restored as a support for the irrigation of local fields.

With the end of the tribute grain system in 1909 and the introduction of modern transportation methods, the Grand Canal project became obsolete.