The book Kaogutu 考古圖 "Illustrated Antiques" is the oldest Chinese description of various antiques. It was compiled during the Northern Song period 北宋 (960-1126) by Lü Dalin 呂大臨 (c. 1042-c. 1090). Lü was actually a philosopher and disciple of Zhang Zai 張載 (1020-1077) and the brothers Cheng Hao 程顥 (1032-1085) and Cheng Yi 程頤 (1033-1107). He was an ardent collector of books and various cultural objects. The highest office he occupied was erudite (boshi 博士) at the National University (taixue 太學). He died before being promoted to an office in the Imperial Secretariat.

The Kaogutu, with a length of 10 juan, is enriched by a sequel called Xu kaogutu 續考古圖 in 5 juan, an explanatory text (shiwen 釋文) to the two parts, as well as a separate inscription called Ke Ji ming 克己銘. Lü Dalin also compiled several explanations of the Confucian Classics.

|

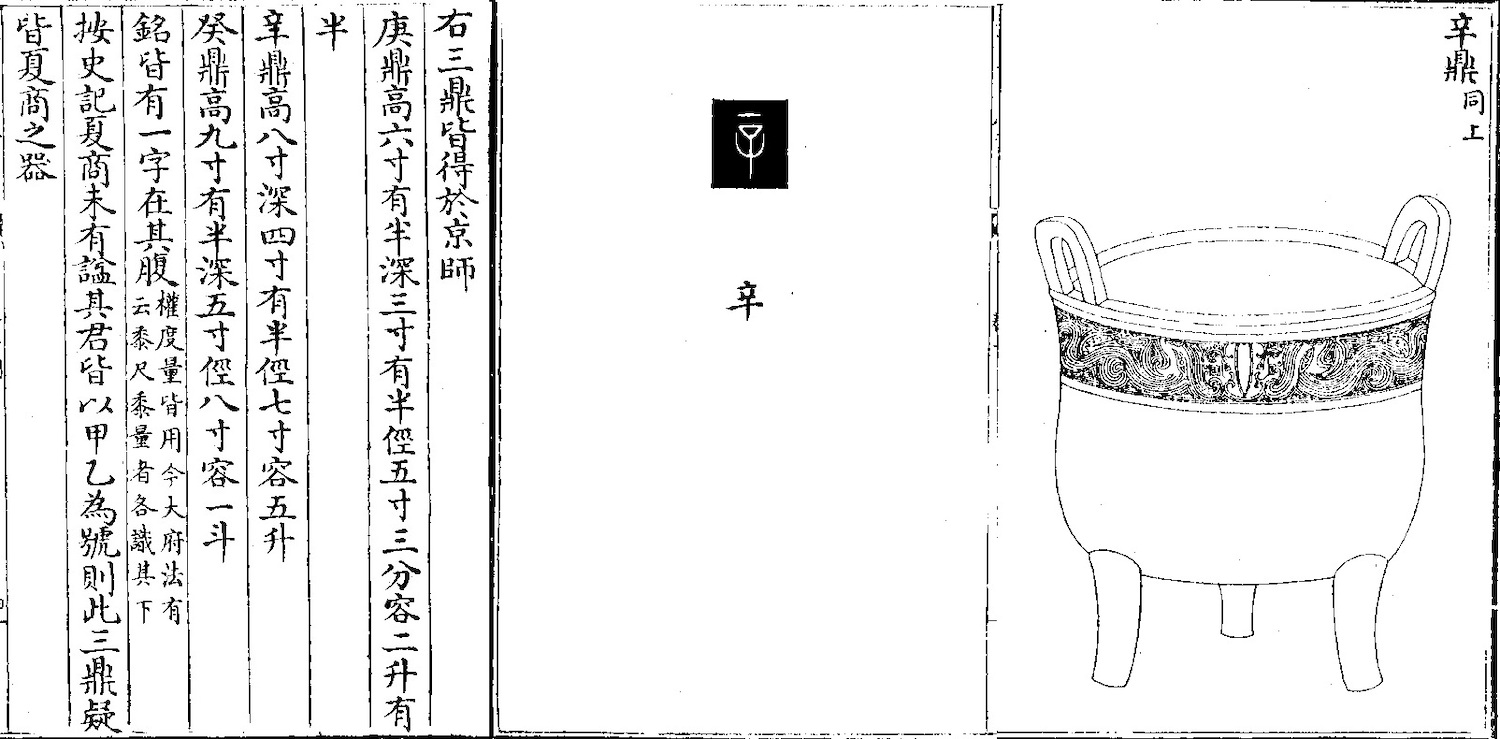

One of three ding 鼎-type tripods, "obtained in the capital [region]" (of the Zhou dynasty). The tripod shown in the figure (Xin ding 辛鼎) has a height of 8 cun 寸 (approx. 8 inches), a depth of 4, and a diameter of 7. The vessel contains 5 sheng 升 (approx. 5 litres). The author remarks that he uses measures according to the standard of the Grand Treasurer (dafu fa 大府法). All vessels bear an inscription of just one character inside the belly (geng 庚, xin 辛, and gui 癸; shown in the middle as a rubbing of the original and a transcription into modern Chinese) inside the belly. As explained in the history book Shiji 史記, the use of posthumous titles was unknown during the Xia 夏 (21th-17th cent. BCE) and Shang 商 (17th-11th cent. BCE) periods. Their rulers were posthumously referred to by Celestial Stems. It can thus be argued that the three vessels can be dated to that period of time. |

His book Kaogutu begins with a critical statement about the ancient Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi 莊子 who despised the Confucians for their love of the past, and at the same time, Lü Dalin lamented the ignorance of his contemporaries towards objects of the past. In the first juan of the book, he describes 18 different tripods (ding 鼎). In some newer editions, the Kong Wen Fu yin ding 孔文父飲鼎 is omitted. In the second juan, 12 hollow-foot tripods (li 鬲) are treated, as well as 6 tripod-and-pot sets (yan 甗), and one piece of a special zan 鬵 tripod. The third juan is dedicated to 16 round vessels (dun 敦), as well as 4 tureens (gui 簋), pots (fou 缶), kettles (fu 鋪) and a cover of a tureen (gui gai 簋蓋). The cover is omitted in recent editions. The fourth juan includes 21 bronze vessels of the yi 彝 type, 8 carry-on-pots (you 卣), 3 zun 尊 vessels, 1 lei 罍 jar, and 14 cans (hu 壺). In recent editions, the sequence of the cans Kaifeng Liushi xiao fanghu 開封劉氏小方壺圖 and Mige fang wen fanghu 秘閣方文方壺圖 is converted. In the fifth juan, 8 beakers (jue 爵) are described, 2 oblong bottles (gu 觚), 2 bowls (dou 豆), 1 lamp (deng 鐙), and several other vessels (he 盉, kui 饋 and yan 瓿). The sixth juan includes 2 plates (pan 盤), 4 footed lades (yi 匜), 1 yu 盂 type pot, and several parts of weapons. The last three juan include bells (zhong 鐘), a sounding-stone (qing 磬) and a chun 錞 bell, as well as a lot of objects of jade or metal from the Zhou 周 (11th cent.-221 BCE) and Han 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE) periods.

All objects are illustrated and described, and for those bearing an inscription (mingwen 銘文), the original appearance of the inscription (seal script) is given as well as a transcription into Chinese standard-script characters.

The sequel Xu kaogutu describes 20 jade objects in the first juan, 22 bronze vessels in the second juan, 26 li 鬲 tripods in the third juan, 20 bells in the fourth juan and 12 other bronze objects in the last juan. In this book, some illustrations are missing. The reason for this might be that Lü Dalin was given a description by someone else without having seen the object itself.

The chapter Shiwen gives explanations to the characters of the inscriptions and the interpretation of the ancient characters.

The Kaogutu, along with the Xu kaogutu was finished in 1092. It is a very careful study of antiques in which the compiler tried to avoid all speculation and wrong interpretation. The various objects had been collected by private collectors as well as by government institutions like the Imperial archives (mige 秘閣), the Office for Imperial Sacrifices (taichangsi 太常司) or the Palace Treasury (neifu 內府). For some objects, the place of excavation is indicated, as well as the time period it was made.

The earliest surviving print dates from the Northern Song period, another old print is that of the Boruzhai Studio 泊如齋 from the Ming period 明 (1368-1644). The print of Master Huang 黃氏 from the Qing period 清 (1644-1911) does not include the Xu kaogutu but instead Zhu Derong's 朱德潤 (1294-1365) text Ji guyu tu 集古玉圖. There are two other Qing-period prints, the Kaogutu by Ding Yusheng's 丁禹生 (i.e. Ding Richang 丁日昌, 1823-1882) Baogutang Studio 寶古堂, and the Xu kaogutu in the Shiwanjuanlou congshu 十萬卷樓叢書.

The Kaogutu is also included in the series Siku quanshu 四庫全書. The copy owned by the Beijing Library 北京圖書館 dates from the Yuan period 元 (1279-1368) and is not very good. The original version of the Boruzhai Studio is also not very good and contains many printing errors. The most widespread version is that of the Baogutang Studio which is based on the Boruzhai version but has been amended on the base of Ouyang Xiu's 歐陽修 (1007-1072) catalogue Jigulu 集古錄 ad Xue Shanggong's 薛尚功 (fl. 1144) Lidai zhongding yiqi kuanzhi fatie 歷代鐘鼎彝器款識法帖.